If there is one thing I have missed more than anything else during the pandemic, it is nightlife. In 2020, at least 22 music venues, including clubs and music-friendly bars and restaurants, shut their doors in the City of Toronto.

As a nightlife person, I was saddened by the closures. There were so many live music venues, especially for Black music, when I was growing up. For instance, I remember seeing acts like Gladys Knight, Kool and the Gang, Lou Rawls and so many others at the Ontario Place Forum.

However, I never saw Eartha Kitt perform, although she came to Toronto frequently during the 1970s and 1980s, singing at venues like the Royal York’s Imperial Room, O’Keefe Centre, and the Forum.

A tweet this past January, by Black Women Radicals, an advocacy organization, offered a reminder of her presence here. It shows an image of Kitt jumping rope with a child, dated May 1, 1966, and photographed by the Toronto Star’s Barry Philp; the image is held by the Toronto Public Library (TPL).

As someone who has spent over a decade working in Black archives, I was shocked that I’d never seen this photo before. I was intrigued by the image, and the window into 1960s Toronto that it opened.

Born Eartha Mae Keith in South Carolina in 1927, Kitt in her twenties danced with the Katherine Dunham Company, founded by Katherine Dunham (1909-2006), one of the originators of modern Afro-Caribbean dance. In 1953, Kitt recorded “Santa Baby,” a song that catapulted her into stardom. Throughout the 1950s, she recorded more music, starred in films and television shows, and performed at nightclubs and on the Broadway stage.

On June 23, 1960, Kitt made one of her first appearances in Canada at Burlington’s Brant Inn, singing songs like “I Wanna be Evil,” from the 1954 film New Faces. Unfortunately, she wasn’t received well by the Star’s then-entertainment writer Antony Perry, who described her as having “no voice, and what vocalizing she does is taut and over-strained. Her notes are flattened and monotonous, almost purposely.”

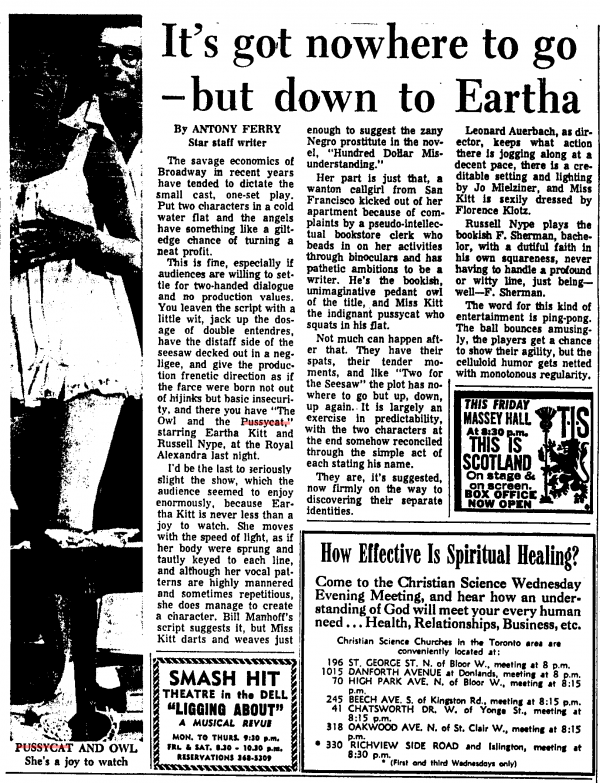

Six years later, however, when Perry reviewed Kitt in a touring production of the Broadway hit “The Owl and the Pussycat,” at the Royal Alexandra Theatre, he rejoiced: “Eartha Kitt is never less than a joy to watch …. She moves with the speed of light, as if her body were sprung and tautly keyed to each line.”

Globe and Mail writer Ralph Hicklin, commenting on that performance, also recounted how Kitt had “endured the description of sex kitten for years in her career as a singer, but she is much more.” “Her voice,” he added, “varies from soprano to contralto, her accent from Martha Raye to Eartha Kitt.”

Importantly, the seven images in the TPL archive of Kitt dated May 1, 1966, capture her at a moment before her fame exploded, and then ascended downward just as quickly.

Kitt’s sex kitten image was supersized in the role of “Catwoman,” on the television series Batman (1966-68), which she played in 1967. Just one year later, however, her career nearly ended when, during a White House luncheon, Kitt spoke out against the Vietnam War. For nearly a decade afterward, she was blacklisted by many in the U.S. entertainment industry, and forced to find work outside the country. That’s why Kitt performed at many Canadian music venues during 1970s.

Against this context, I wanted to know where and why those images, which never actually appeared in the Star, were taken. To solve this mystery, I tracked down the Star’s photographer, Barry Philp, who now lives in Prince Edward County.

After finding a post on Facebook about his book Life’s Dance: A Scrapbook of Prints and Poems, I also contacted his publisher, Books & Company in Picton, Ont., and then arranged a call with Philp about that moment, 56 years ago, when he photographed Kitt.

“Eartha Kitt was here in town. She was probably singing at the Royal York Hotel. A reporter, George Bryant, and I went over to The Four Seasons [Motel], and we met up with Eartha Kitt. That picture was taken in the courtyard at the back,” recalled Philp in a phone interview. He told me that Kitt was in a great mood, playing with her daughter, Kitt Shapiro, and their dog. Philp could not remember the identity of the other young girl who appears in one of the photographs. The reporter, George Bryant, passed away in 2013.

The Four Seasons Motor Hotel was a hot spot for celebrities in the 1960s. Opened in March 1961 at 415 Jarvis Street just north of Carleton, the Four Seasons was a ground-breaking advancement in hotel lodging at the time. The Jarvis Street location, now a townhouse complex, was the first in the Four Seasons chain of hotels. The second, Inn on the Park, at Leslie and Eglinton Avenue East, opened in 1963. The Motor Hotel took Toronto-born Isadore (Izzy) Sharp five years to build.

Jamie Bradburn’s Tales of Toronto blog explains that the street had been lined with the homes of wealthy Torontonians before the 1950s. But by the time Sharp built his hotel, “[Jarvis] had a reputation as a hangout for derelicts, drug dealers and prostitutes.” That is why architects Peter Dickinson Associates designed the 125-room motor hotel with an inward-facing orientation, with a restaurant, bar, and guest rooms overlooking a garden courtyard with a pool. For a time, the hotel was considered a modern oasis in the city.

As the Globe and Mail noted in a 1971 feature, the Four Seasons Motel Hotel was “[n]o architectural gem, [but] it is nevertheless an almost perfect example of the Early Sixties motor inn, spare, compact, and non- rather than un-pretentious.”

In 1976, the hotel was leased to another chain. In 1989, it was demolished to make way for residential housing.

We know that Kitt had been in Toronto in May of 1966. The reviews for “The Owl and the Pussycat” in both the Star and Globe and Mail are dated May 10. The TPL told me that photographic research at the library is dependent on stories that ran in the Star. Unfortunately, the only information they have of the shoot are scans of the image’s backside, which lists photographer, month/year, and this note: “Eartha Kitt with daughter in Toronto.”

Further, the librarian who recorded the images at the time would have had to work with what was stamped on the image. If they had been published in the paper, a librarian would have cut out the caption from the Star, glued it to the back of the image, and affixed a specific publication date.

These images of Kitt speak to the importance of archiving and record keeping. Photographs of the past only hold weight in the present when there is identifiable information to connect the subject(s) and/or place(s) captured at that moment in history.

There are countless images of Black entertainers who came to Toronto during the 1960s through 1980s, whose photos were taken but were not written about by mainstream media outlets. To choose just one example, another photograph in the TPL archive shows Lena Horne standing outside the Royal Ontario Museum in 1974. It is also shrouded in mystery, waiting for someone to unlock its story.

Eartha Kitt died in 2008. What I wouldn’t give to have seen her live at a venue in Toronto. However, next time I walk by 415 Jarvis, I will have the memory that Kitt once jumped rope with her daughter (and their dog) there. That’s a pretty cool close second.

Cheryl Thompson is an Assistant Professor in the School of Performance at Ryerson University. Her latest book Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty was published in 2021. Follow Cheryl on twitter at @DrCherylT.

The post Black History Month: Eartha Kitt’s forgotten visits to Toronto appeared first on Spacing Toronto.