When Douglas Counter heads out the front door of his Etobicoke home to appreciate the day’s new blooms, he doesn’t have to go far. The flowers are waiting for him right in his yard, including the city-owned boulevard beside the road.

Like many in Etobicoke, his boulevard is a drainage ditch. But in his, native wildflowers, sedges, and grasses have replaced the traditional sloped turf lawn. They’re not there by happenstance. Counter not only nurtured each plant with love, but he has also fought for their right to be there.

Why? There are several reasons. But one has to do with his local neighbourhood beach at Marie Curtis Park.

Counter, now over 60 years old and a former director of the North American Native Plant Society, has lived in this same Etobicoke home since childhood. For decades, he’s watched Marie Curtis Park Beach be deemed unsafe for swimming by the City of Toronto.

Eight out of 10 beaches in the City currently meet Blue Flag qualifications, an eco-award for high standards for water quality, environmental management, environmental education, and safety. Marie Curtis Park Beach does not.

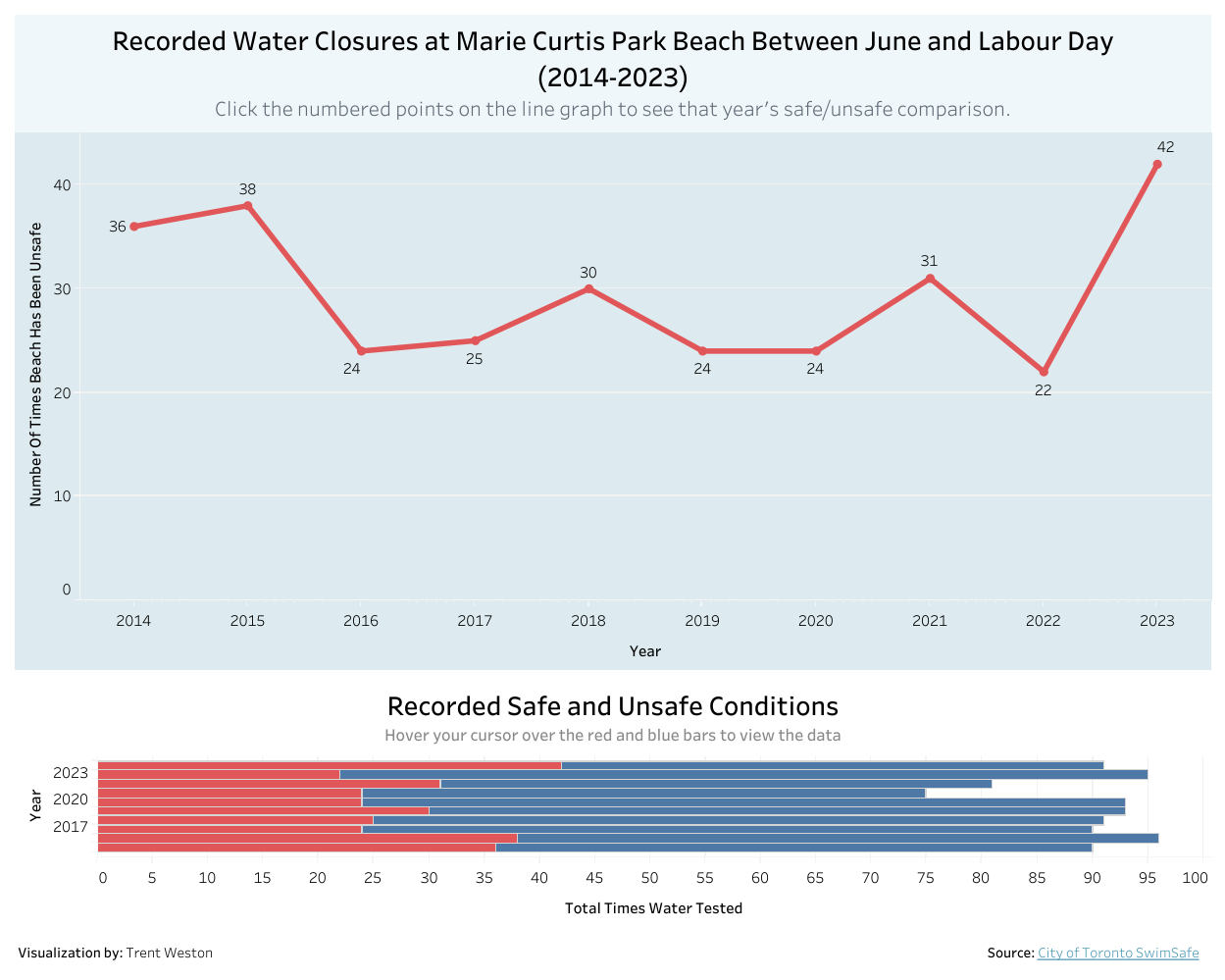

Between 2019 and 2023, people have been advised against getting in the water at Marie Curtis Park Beach 143 times, according to available data. That’s a lot, especially when the water has only been tested 435 times during this same period. The City only tests the water between June and Labour Day, a little over three months of the year.

Many of these closures are the result of stormwater runoff. In the words of the City of Toronto:

A major source of water pollution is stormwater runoff, which may contain harmful bacteria, pathogens, heavy metals, oils, and pesticides, as well as nutrients that can increase algae growth and degrade the health of Toronto’s waterways. When stormwater runs off, it makes its way into the nearest creek, river or storm sewer, picking up debris, including what is on our roofs, roads, cars and sidewalks, before discharging into the nearest waterway. This includes grease, bird/animal droppings, pet waste left on sidewalks, garbage, bacteria and other pollutants.

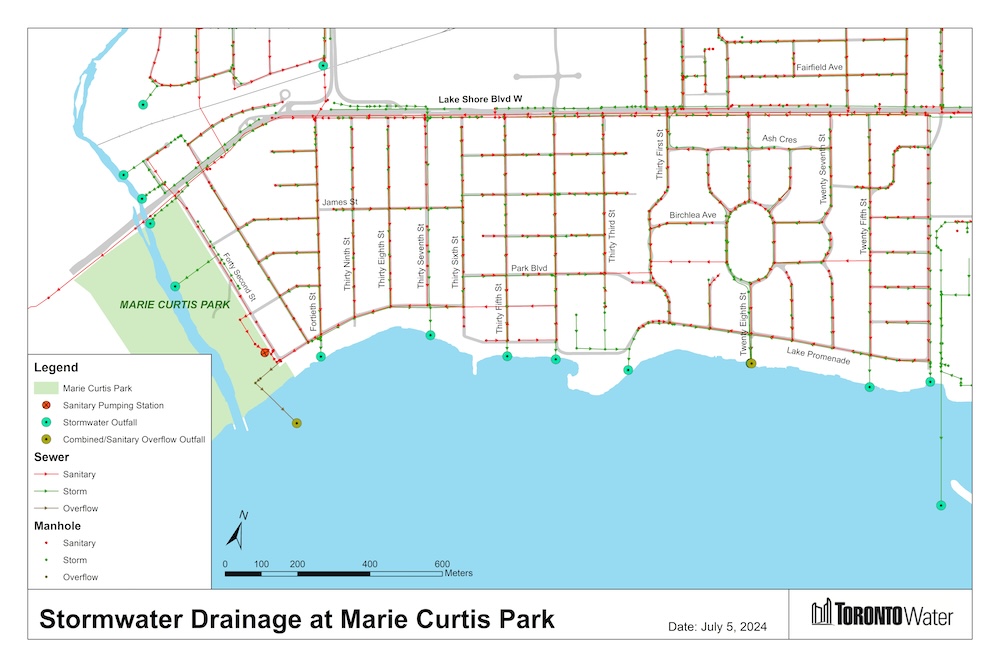

One of the main reasons Marie Curtis Park Beach has yet to achieve Blue Flag status is because it’s connected to the mouth of Etobicoke Creek. During periods of intense rain, stormwater runoff channels from the storm sewer system into the creek.

But what could Counter, as an individual, do to help water quality at Marie Curtis Park Beach? He can’t stop torrents of rain from rushing into the lake at his local beach. Well, actually, as it turns out, he can. And he does.

It all began in 1998, when Counter read recurring local news items about beach closures following major storm events. He fondly remembered stories his father would tell him of what it was like swimming at Sunnyside Beach every summer as a child growing up in Parkdale. As this was something Counter was unable to experience in his childhood and often still couldn’t do today, he contacted the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) to learn more about what was happening. Specifically, he was curious to find out where the water from his drainage ditch went.

Counter obtained a drainage map, which allowed him to track where the rainwater on his street was going.

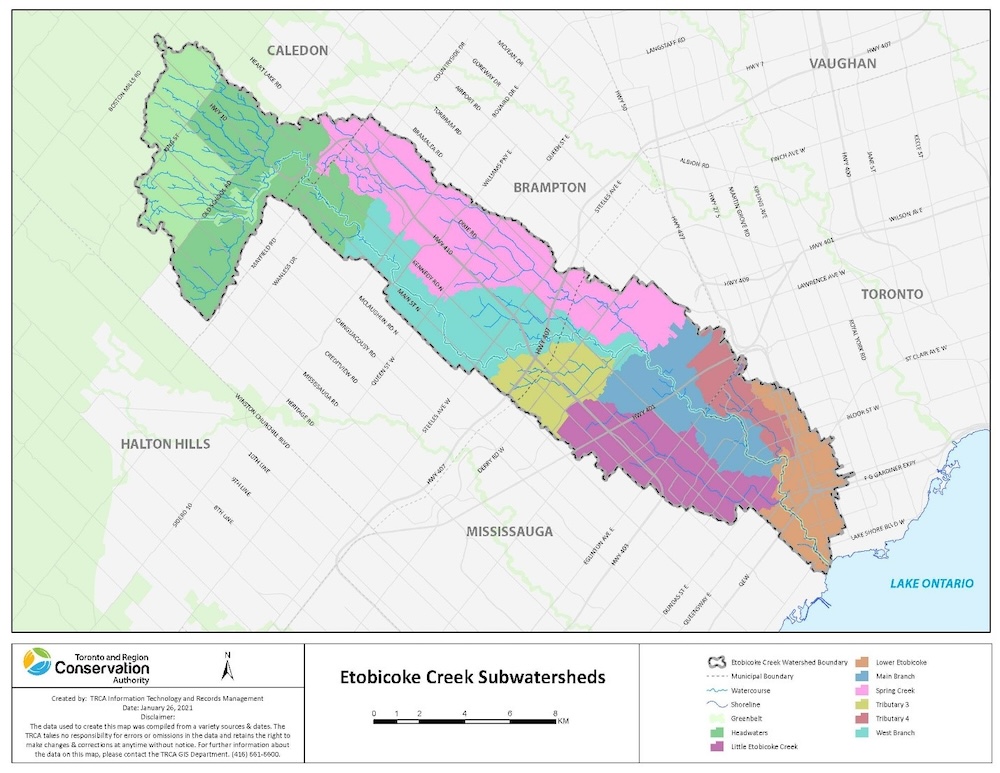

Fallen rain from downspouts, driveways, sidewalks, gardens, and the road collected in drainage ditches. It then flowed into next-door neighbour’s drainage ditch, and then the next, and so on. As the water flowed along these ditches, it increased in volume and speed as it made its way down the street and into a connecting neighbourhood, until it entered a storm sewer drain. About a kilometre away from this drain, the water resurfaced at a large stormwater outflow culvert and entered Renforth Creek. This small tributary then flowed its way into the larger Etobicoke Creek. And the water didn’t stop there. Etobicoke Creek flowed and flowed and flowed until it entered Lake Ontario.

Where?

At Marie Curtis Park Beach.

And what does the flowing water bring with it? An abundance of pollutants and waste, all of which can contribute to heightened E.coli levels at the beach, and subsequent closures.

“I realized that my ditch, even though it’s several kilometres away, is directly connected to that issue at the lake.”

Why Garden

As an active conservationist, Counter was always looking for ways to help bolster environmental protection using naturalist methods. The four-by-13-metre drainage ditch in front of his property became his next project.

“I decided to create a stormwater infiltration garden in the public city-owned boulevard to show people in my community that they could have a positive impact on the quality of the lake and streams through the way they gardened.”

Many boulevards in Etobicoke look like Counter’s before he transformed it. They’re sloped drainage ditches with densely compacted soil and turf grass above.

After contacting the TRCA and conducting further research, in the spring of 1999 Counter turned his traditional drainage ditch into something different. He sowed it full of native plants, including swamp milkweed, ironweed, blue vervain, blue flag iris, and Eastern wild columbine. The result was that it became home to an abundance of wildlife, such as birds, grasshoppers, crickets, Monarch butterflies, and other pollinating insects.

The drainage ditch not only acts as a functioning habitat, it’s also a natural water filtration system.

Counter explains that since planting the garden, the soil quality has improved dramatically, and stormwater absorbs into the ground instead of flowing toward the creek. The native plants in Counter’s ditch garden have created a more permeable soil than a turf lawn, with its very shallow, dense root system. Once the water is in the soil, plants can then absorb the contaminated water. Pollutants are then either stored in the flora’s tissues, transformed into less harmful substances, or even fully metabolized.

“The garden basically is acting like a sponge.”

The native plants that Counter has used in the ditch also cleanse water through adsorption, which is when pollutants physically cling to the plants themselves. These plant roots can have a large surface area, and act as a magnet to capture pollutants from flowing water. The roots often harbour beneficial microorganisms, which help to break down pollutants and clean the water.

“There is virtually no runoff from my ditch, and my ditch does not flood. It basically allows the water to slow down and absorb into the soil, and be cleansed through that process.”

Now, Counter says, the water that leaves his property is cleaner than when it arrived. And the amount of water leaving his boulevard is significantly lower – a small trickle even during significant downpours. That means Counter’s property is one less source of pollution at Marie Curtis Park Beach.

“It’s amazing, and that’s just one property. If all the properties on my street did that, imagine how healthy the community would be; it would be amazing.”

Counter’s unearthed solution had the potential to help heal the beach, but unbeknownst to him, it would also lead to a lengthy court battle.

From Complaints to Court Dates

Even though Counter started his native plant pollinator garden back in 1997 as a memorial to his mother, whom he lost to cancer, it wasn’t until after his garden extended onto the City boulevard in 1999 that the trouble started. The boulevard was the last section to be reinvigorated with native plant species, after he had already altered his front and back yards.

In the summer of 2000, Counter started to receive by-law violation notifications about his ditch garden. After a series of minor nuisance complaints, which Counter remedied and had approved by City inspectors, someone complained that the garden allegedly blocked sightlines from a neighbouring driveway. The complaint notifications were issued to Counter with a clear message that he had to remove the garden in order to be in accordance with City by-laws. But Counter felt his garden was already well within City guidelines – especially regarding plant height. Counter says no-one ever came by to measure the plants’ heights, which he believed were well within by-law regulations.

Throughout the summer and autumn, Counter repeatedly received communications from the City telling him to remove the stormwater infiltration garden. The City had deemed the garden an illegal encroachment, and thereby subject to an encroachment permit. The application for the permit would cost $700, with an additional annual property tax fee of $630 – ten dollars for every square metre of city land occupied. There would be a $2,000 fee if he failed to comply.

Eventually, in late September 2000, workers from the City of Toronto arrived to cut down the ditch garden on his boulevard. Counter and his father, Victor, whom he lived with at the time, requested a copy of the by-law the garden was allegedly violating. When the workers failed to produce the by-law infringement, the Counters objected to the cutting of the garden.

At 75 years old, arthritic and with no shoes on, Victor told the workers he would chain himself to the fence to prevent the garden’s destruction. Police arrived at the scene and told the workers to disperse.

After this failed attempt to cut the garden, the City sent Counter an open-ended ultimatum: they would be back to cut the garden when weather permitted.

Counter constantly feared that he would come home, and the garden would be gone. Every day, he felt sick to his stomach, thinking that today could be the day he would lose his plants. That all his work could be for naught. This fear motivated Douglas and his father, Victor, to file a lawsuit.

The Counters were also prompted to file a lawsuit by the sizable permit fees and potential fine. They felt it set a dangerous precedent that would discourage anyone else from creating naturalized stormwater infiltration gardens.

“This was a demonstration. I wanted to show the community this was a way that they could help improve water quality in the beach, and I wasn’t prepared to remove it.”

Counter v. City of Toronto (2002) claimed that the City violated the Counter’s constitutional right to freedom of conscience, religion, and expression guaranteed under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The case resulted in the court recognizing that, on public land that homeowners are required to maintain, citizens have the right to tend to a naturalized garden as a protected expression under the Charter. This extended the existing case law from protecting such gardens on private property to also include privately maintained public property, like boulevard ditch gardens, for the first time in Canada.

“I have to maintain this property. I want to do it in a way that is environmentally responsible,” says Counter.

Flowing Towards the Future

David Kellershohn, Associate Director, Engineering Services at the TRCA, says, “While infiltration gardens can improve water quality and can relieve stress on sewer systems, constructing enough of them and locating them correctly within a built urban environment would be challenging.”

However, green infrastructure projects, including stormwater infiltration gardens, are part of the City of Toronto’s plan (PDF) to enhance water quality. The City of Toronto’s How You Can Help Manage Stormwater page also cites these gardens as a way to manage runoff.

Counter believes getting citizens to construct their own stormwater infiltration gardens could help address the challenge, but wants to see more action from the City of Toronto. He feels incentives such as tax rebates for people creating rain, wetland, or stormwater infiltration gardens to help manage runoff could be a potential way for these gardens to become more mainstream.

Conversely, if the City can’t provide incentives in the form of a rebate, then perhaps a stormwater runoff tax could help address the situation. This tax could be based on the amount of runoff that leaves one’s property, says Counter.

Toronto has previously considered this concept, in the Stormwater Charge and Water Service Charge Consultation, but the proposal was paused. However, due to the significant rainfall and flooding Toronto has experienced this summer, City Council is once again contemplating a stormwater charge. It promises the potential charge would not be levied on homeowners, and would instead only affect industrial and commercial properties.

Still, Counter is frustrated that what he’s proven can work, through his project on his own boulevard, isn’t being encouraged elsewhere.

“Here we are 25 years after I started this boulevard garden just to improve the lake quality at Marie Curtis Park Beach, and I’m really disappointed to see that there’s no substantial change.”

Counter regularly conducts garden tours at his home, gives talks, and runs workshops to promote biodiversity and the impacts residential gardens can make in helping the environment.

Moving forward, Counter hopes the City will try a demonstration street filled with boulevard rainwater infiltration gardens to help manage stormwater runoff. He points to the example of Seattle and its Street Edge Alternatives Project.

As he says, “The scale of my garden, if it was multiplied by hundreds, would make a tangible difference.”

And it can all start with individual efforts. “It’s possible. One person can make a difference. That’s what I want to impart. You can make a difference by doing this.”

Photos by Trent Weston unless otherwise specified.

The post From drainage ditch to vibrant, pollution-absorbing habitat appeared first on Spacing Toronto.