It’s easy to overlook the Donald D. Summerville Olympic Pools.

Despite its sturdy presence on Lake Shore Boulevard East, the futuristic elevated pool complex at Woodbine Beach looks dirty and ramshackle.

Due to years of careless treatment by the city, the exterior is cluttered with ugly storage cages and random detritus and the surrounding grass is patchy and untended. Even the Pizza Pizza stand and police station built into the exterior have seen better days.

Inside the situation isn’t much better. The changing rooms are dank cinderblock labyrinths and the whole thing feels temporary and generally unwelcoming.

All that changes up on the swimming deck. The main Olympic pool is perched among the tree tops and boasts a panoramic view of the beach and Lake Ontario. Under the evening sun the place looks crisp and stylish.

The idea to build an Olympic swimming pool in Toronto dates back to a 1955 report by City of Toronto parks commissioner George Bell, which suggested building a simple community pool at Kew Gardens.

Rather than overhaul a landscaped neighbourhood park, controller (and later mayor) Donald D. Summerville proposed an Olympic pool at Woodbine Beach, where there was in theory more space.

At the time, no Canadian city had hosted an Olympic games, and Toronto was quietly mulling a bid for a major sporting event, possibly a world swimming championship. The new pool would therefore be an important addition to the city’s sporting infrastructure.

In October, 1961 the now-defunct Metropolitan Toronto government transferred the land on the south side of Lake Shore Boulevard East at Woodbine Avenue to the City of Toronto for the purposes of building a “double-size” pool.

The city retained architects George Everett Wilson and Frank D. Newton to design the building, but the pair quickly found the project was far from straightforward. Firstly, the ground was an unstable mix of sand and sanitary fill, which required watertight caissons to be sunk 18 metres into the ground.

To make matters worse, underground utilities cut across the site in multiple directions, constraining the usable footprint on all sides unless the city committed to a costly process of relocating the pipes and cables.

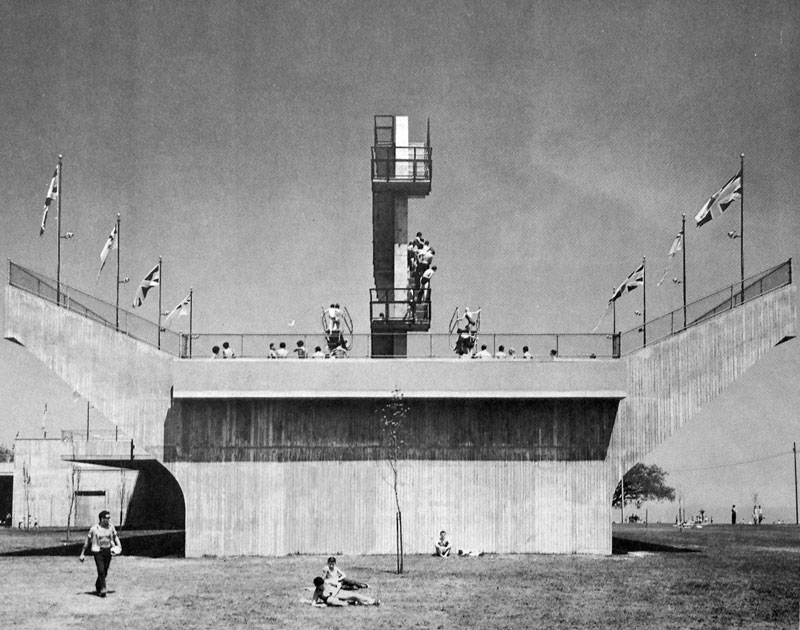

The arms of the Donald D. Summerville Olympic Pools were designed by architects Wilson + Newton to avoid relocating utility pipes. Image: Wilson + Newton architects.

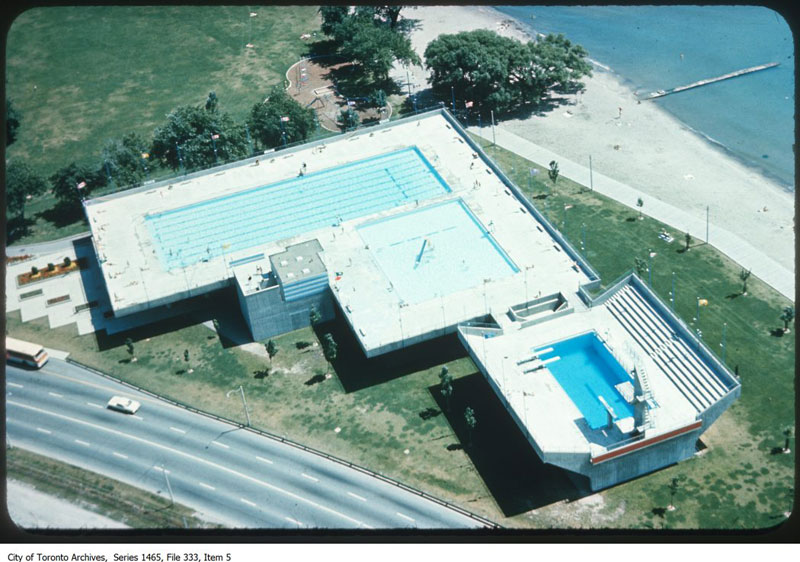

The solution devised by Wilson + Newton placed the various swimming pools above the changing rooms and cantilevered the sun decks and bleachers out over the utility lines, creating the building’s distinctive y-shape. The Toronto Daily Star called the design a “sky swim” and noted the elevated pools were likely a Canadian first.

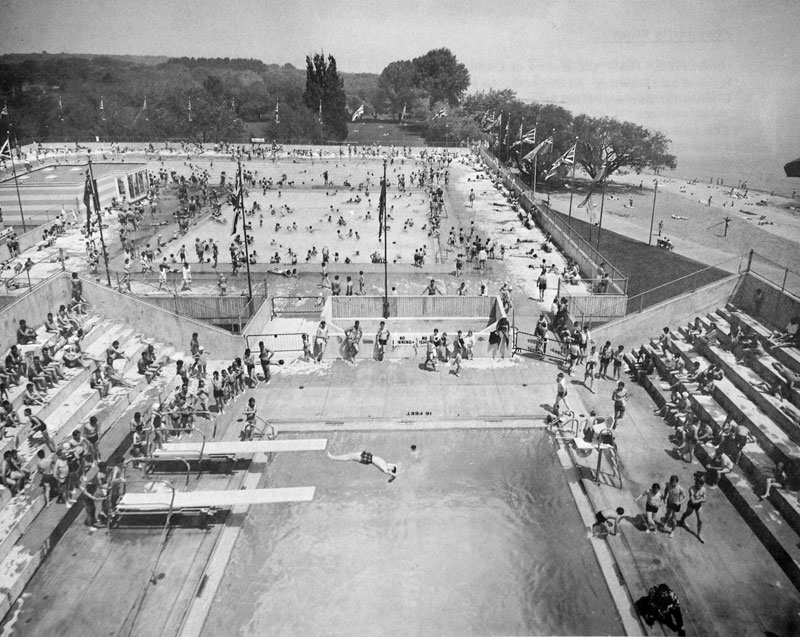

The complex, which was to be built in two back-t0-back phases, consisted of a 50-metre Olympic pool, a shallow wading pool, and a diving pool with 10-metre high dive. Despite the city’s sporting ambitions, the Beaches pool was designed without high-capacity grandstands.

City parks commissioner George Bell said adding permanent seating for an Olympic-sized crowd would be “folly,” Instead, he said the capacity could be added later, if necessary, using temporary bleachers. “Toronto might get the Olympics once in 50 years,” he said.

Construction started on January 8, 1962 with the expectation the pools would be open for use by the summer. However, by May, 1962 it was clear the project was running behind schedule. The opening date was pushed from July 1, to August 1, and then September 15. By November, the unfinished pool was beginning to become a point of frustration for locals.

1962 was a municipal election year, and Ward 8 aldermanic candidate John Square used the state of the unfinished pool to attack the incumbent city controller, Philip Givens.

“Ward 8 is the most forgotten area in the whole city,” Square said. “All you have received for your taxes in the last 10 years is a lousy swimming pool. It is a frozen asset that isn’t even finished yet.”

Square lost his election bid, but former Beach alderman Donald D. Summerville was elected mayor.

The Globe and Mail reported the delay was largely due to a “a combination of circumstances and a lack of co-operation between different city departments.”

In the months leading up to opening day, the Toronto newspapers fixated on the potential for traffic problems and the lack of available parking spaces near the new 1,700-person capacity complex.

In the Globe and Mail, Metro traffic engineer Sam Cass rejected calls for a new parking garage at Woodbine Beach, citing the prohibitive cost.

“Many people who come to the area now, including those who come to use the swimming pools, will have to come by public transit—at least we hope they will.”

“We provided 440 parking spaces for that pool and that’s enough,” said parks commissioner Bell. “Some people around this city wouldn’t be happy until we went ahead and turned the whole park area into parking space.”

The Beaches Olympic Pools opened a year behind schedule on June 1, 1963. As the naysayers predicted, the first day was mired in traffic problems. The jam on Lake Shore Boulevard East reached the intersection with Queens Quay, in part due to detours related to construction of the Don Valley Parkway, while police stationed outside the pool tried to direct cars away from the overtaxed parking lot.

Up on the pool deck, 500 people eager to take their first dip in the water were held at bay for almost two hours of ceremonies and swimming and diving demonstrations.

When the show was finally over, “corpulent” Ward 5 alderman Joseph J. Piccininni, who was clad in a striped bathing costume, was the first to leap into the water from the diving platform.

The raised deck of the Donald D. Summerville Olympic Pools allowed for sunbathing and provided panoramic views over Lake Ontario. Image: Wilson + Newton architects.

During its first months of operation, the Beaches Olympic Pools and others operated by the City of Toronto proved exceptionally popular, especially with interloping swimmers across the municipal border in Scarborough.

In the 1960s, parks and recreation facilities were the financial responsibility of the various towns, townships, and cities that made up Metropolitan Toronto.

“Mr. Bell said he was sure that a number of suburban tans—or sunburns—were acquired in the eight swimming pools provided free by the city [of Toronto,]” reported the Globe and Mail.

“Sure it’s unfair,” said Bell. “Taxpayers in the city go to these pools and find they’re filled up with people from Scarborough or somewhere. Toronto is taking a trimming on these things, but what can we do about it … check everyone’s name in the city directory?”

“Amalgamation is the only way of settling it,” he said.

The Donald D. Summerville Olympic Pools represented Toronto at its most extroverted. Image: City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, Series 1465, File 333, Item 5.

In November, 1963 mayor Donald D. Summerville died of a heart attack and the pools were officially renamed that same month in his honour. Summerville was a long-time Beach resident and a prominent booster of the pool project.

Though the complex was undoubtedly pretty, the lack of a roof made it only suitable only for summer use. In 1969, the city again commissioned Wilson + Newton to explore options for covering the pool.

Their report weighed the benefits and drawbacks of a massive Buckminster Fuller-style geodesic dome (too costly to heat,) an air-supported structure (too dangerous,) and a futuristic triodetic structure (too expensive) against more conservative options, such as a simple soft shell or cable-supported roof.

Ultimately, Wilson + Newton recommended a simple steel frame roof that could be attached to the existing pool deck for about $972,000, but it was never built.

Perhaps that was for the best. One of the best features of the Donald D. Summerville Olympic Pools is its unbroken views of Lake Ontario and its sun drenched bathing areas.

Now 53 years old, the pool is beginning to show its age. The city began a $3.75 million renovation in 2013 that rectified structural issues and made minor cosmetic improvements to the public facilities, but the project didn’t address the trashy and unwelcoming exterior.

It’s a shame, because the popularity of the pool in the 1960s was clearly the result of the architecture. From the sunbathing and swimming deck, the pools offered unbroken views of Lake Ontario that were unavailable anywhere else in the city.

In some areas the pool water appeared to blend with Lake Ontario and stretch to the horizon like an infinity pool in an exclusive club or expensive hotel. The Summerville pool told the public it deserved great facilities, too.

In spite of its problems, when the sky is blue, and the pool is blue, and the lake is blue, the Donald D. Summerville pool still looks like the Côte d’Azur.

The post Toronto’s Summerville pool is a slice of the Mediterranean appeared first on Spacing Toronto.