Peter Dickinson was dying when he designed the Inn on the Park.

From a bed in Mount Sinai hospital, his body weakened from cancer, Dickinson listened to Four Seasons co-founder Isadore Sharp explain his idea for a new flagship location at Leslie and Eglinton.

Sharp’s sixteen acre site was directly opposite the west branch of the Don River, next to Sunnybrook and E. T. Seaton parks, and rose gently to a hill in the middle. It was outside the core, but Sharp hoped to lure guests to the picturesque location.

After securing the land, Sharp approached Dickinson, who had previously designed the company’s first motor lodge on Jarvis and Carlton streets.

The hotelier explained he could only afford to build a 200-room complex, but that the design should be able to accommodate expansion.

“He sketched on a pad the way the hotel looked when it opened,” Isadore Sharp told Globe and Mail architecture columnist, Adele Freedman. “This building, when it opened, was identical to the sketch.”

The Inn on the Park as it appeared on opening day. The east block would later be expanded and a tower built at the rear of the site. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 70, Series 330, File 551.

Peter Dickinson was born into a wealthy family in London, England in 1925. He went to the prestigious Westminster School and, aged 17, enrolled in the Architectural Association school in Bloomsbury. A tall, powerful man well over six feet and 220 lbs, he loved to drink and smoke.

Dickinson’s studies were interrupted by military service during the Second World War. He served as a lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards, but seriously injured his knee during a training exercise. In November, 1945, he was out of the military and back in school.

In 1946, Dickinson won the Architectural Association’s fourth year prize, which was presented by that year by Frank Lloyd Wright by virtue of it being the school’s jubilee. The next year he took the fifth-year prize and graduated with honours in 1948 before being elected to the Royal Institute of British Architects in February, 1949.

One of Dickinson’s first post-graduation designs was a competition entry he submitted to the Festival of Britain, a major exposition held in London in 1951. The blueprint called for a 300-foot steel and concrete column capable of spraying coloured jets of smoke.

The concept building won third prize—the winner was the famous Skylon—but it impressed Forsey Page, the co-founder of Toronto residential architecture firm Page and Steele, when Dickinson interviewed for the job of chief designer at the firm.

According to Adele Freedman in her book Sight Lines, Page frequently hired young British architects. “They came cheap and worked hard,” she wrote. “A background in the forces was essential: it said a man could get a job done.”

Dickinson traveled to Halifax with his wife, Vera, aboard the RMS Franconia in 1950. From there they boarded a train to Toronto, arriving at Union Station on May 13.

Dickinson told Mayfair magazine in 1957 that he and Vera walked out of the Beaux-Arts Great Hall, up Yonge Street past construction of the country’s first subway line, to Bloor Street where they stopped a policeman to ask when they would reach the centre of the city.

“Mile after mile of small, sordid—even squalid—buildings; that was the centre of the city we’d come to live in,” he exclaimed.

He was only 24.

Yonge Street as Dickinson would have experienced it on his arrival in Toronto. The subway was still four years from completion. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds, Series 281, File 44.

He might have not liked what he saw, but something about Toronto and Canada spoke to Dickinson. “When we hit this county he found himself,” Vera would later recall to Adele Freedman. “He found his level, he found his soul, he found his self worth.”

At Page and Steele, Dickinson stood out as a committed modernist in a firm that specialized mostly in Georgian Rival-style homes. One of his first assignments was an apartment building for developer Leon S. Yolles on Avenue Road in 1955.

The result, the Benvenuto Place Apartments, is perched on a rise in the road a few blocks south of St. Clair Avenue. All cream brick, airy balconies, and big glass windows, it stood out like a crisp, freshly pressed shirt among its older neighbours when it opened.

After Benvenuto, Dickinson’s rise was positively meteoric. Between 1950 and 1955, he completed approximately 20 projects, including 111 Richmond Street West, the Toronto Teachers College at 951 Carlaw Avenue, and Beth Tzedec Synagogue at 1700 Bathurst Street.

He was known to constantly sketch new buildings, even when entertaining at the apartment he shared with Vera. It was through this constant stream of creativity he developed his signature details: big, gravity-defying entrance canopies and the scissor stair—two interlaced sets of steps in a single well.

As a rising star on the Canadian architectural scene, Dickinson soon outgrew Page and Steele. Despite mounting tension in the office, his last buildings for the firm—the troubled O’Keefe (now Sony) Centre, the Juvenile and Family Court on Jarvis Street, and the now-demolished tower buildings in Regent Park—were well received, with the latter winning a Massey silver medal in 1958.

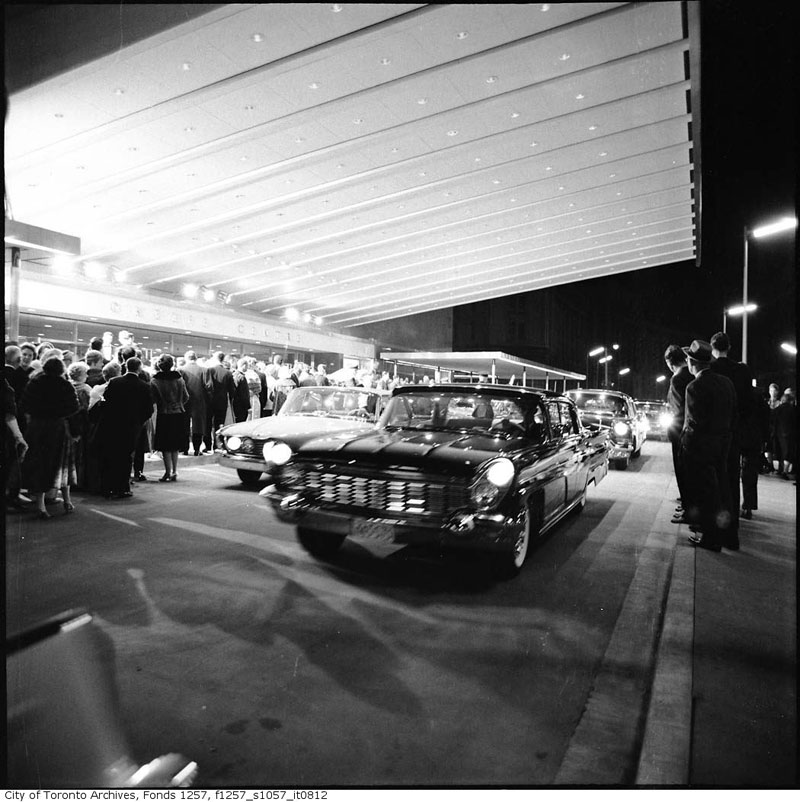

Though the O’Keefe Centre project was heavily scaled back, the auditorium on the south side of Front Street retained one of Dickinson’s signature features: the gravity-defying entrance canopy. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 812.

Frustrated by politics around the O’Keefe Centre (the project was radically scaled back from its original form) and denied a partnership stake in Page and Steele, Dickinson quit to form his own company in 1958, taking with him a number of architects, including Colin Vaughan (father of MP Adam,) and several clients.

Based at Yonge Street and Davisville Avenue, Peter Dickinson Associates designed the soon-to-be-demolished Regis College and the Prudential Building at the northeast corner of King and Yonge in 1960.

“When he started Peter Dickinson Associates,” recalled Colin Vaughan to Adele Freedman, “it was design, design, design. He was working day and night at it, and it was exciting. But as time went by it became: ‘How can I beat the other guy?'” He increasingly often sketched buildings on napkins, envelopes, and cigarette packets to the annoyance of his associates.

Roderick Robbie—future designer of the Canada Pavilion at Expo ’67 and the Skydome—joined in 1959, the same year Dickinson began his association with Isadore Sharp, the co-founder of the Four Seasons hotel chain.

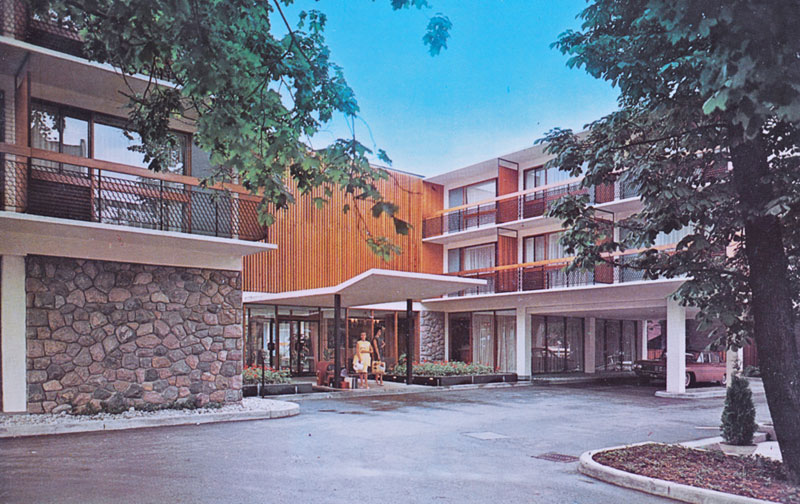

Sharp paid Dickinson $11,000 to design the Four Seasons Motor Hotel on Jarvis Street, just north of Carlton. It was to be a the company’s first location—a suburban motel in an urban setting, something fresh and airy in the staid old heart of Toronto.

The result was a two storey wrap-around building that protected an interior courtyard with a swimming pool. The white-painted brick building had California redwood and fieldstone accents. Clearly impressed with the result, which won a Massey medal in 1961, Isadore Sharp commissioned Dickinson to design his home on Green Valley Road in York Mills.

The Four Seasons Motor Hotel on Jarvis Street—the first location for the soon-to-be international chain—was designed by Peter Dickinson. He would reprise his role as hotel designer on his deathbed. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 70, Series 330, File 551.

Peter Dickinson Associates’ largest commission was undoubtedly the Montreal headquarters of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce in Windsor Plaza.

The design process, however, was fraught with trouble. As he had done countless times previously, Dickinson cut a deal with the developer that didn’t represent good value for his own firm. According to Adele Freedman, he charged just $750,000 for the design, including engineering, on the $25 million building.

Dickinson also frequently clashed with Neil J. McKinnon, the president of CIBC, who was adamant the finished tower be taller than Place Ville Marie—the headquarters of the Royal Bank of Canada that was under construction nearby. “I resisted it, Peter Dickinson resisted it,” the developer, Jack Cummings, told Freedman. “McKinnon was an animal.”

The 43-storey building, completed in 1962, was briefly the tallest in the Commonwealth, but Place Ville Marie displaced it within a year.

Things started to unravel for the high-flying Englishman in 1960. Colin Vaughan, Rod Robbie, Richard Williams and two other associates quit to form their own firm when Dickinson refused them a partnership in the firm. In their place, Dickinson appointed Peter Webb, Boris Zerafa, Rick Housden, Rene Menkes, Peter Trion, and Jack Korbee.

It was also around this time that Dickinson began to suffer from frequent bouts of severe stomach pain. By the time he saw a doctor and was diagnosed with bowel cancer, it was too late. The diagnosis was terminal, and the star architect was confined to a bed at Mount Sinai Hospital.

The Eglinton and Leslie site of the Inn on the Park in 1960. Murray Koffler, one of the founders of Four Seasons, convinced the company to purchase the site for a new flagship location. City of Toronto Archives, Series 12, Fonds 1960, Item 107.

As all this was unfolding, Isadore Sharp was once again considering Dickinson for the job of designing the flagship location in his burgeoning Four Seasons empire. Murray Koffler, a co-founder of Four Seasons and brain behind Shoppers Drug Mart, had spotted a site for sale at Eglinton and Leslie and was immediately convinced of its possibilities.

Sharp and other executives weren’t so sure, but Koffler won them over.

“I was now envisioning another new type of hotel: a resort within a city, a two-hundred-room hotel with a pool and a courtyard surrounded by parkland,” Sharp wrote in his book, Four Seasons: The Story of a Business Philosophy. “But most of the people I talked to were unenthusiastic; they figured it was too far out, in more ways than one.”

Due to his failing health, Dickinson turned the project over to associate Peter Webb. The result was “a y-shaped building: three storeys, two hundred rooms,” which Sharp disliked. He went back to Dickinson.

“This is a resort. We need something attractive,” he said. “Something so architecturally dramatic that people in Toronto and nearby cities will drive all the way to North York to see it.”

“Leave it with me,” Dickinson said.

Isadore Sharp, the co-founder of the Four Seasons chain, loved the angles Dickinson designed into the Inn on the Park. The rooms were joined together at 30, 60, and 120 degree angles. City of Toronto Archives, Series 2, Fonds 607, File 164.

When Sharp returned, Dickinson presented the Inn on the Park on a sketch pad. “Two low wings with dramatic concrete prows like those of a ship, backed by a six-storey tower. It was magnificent. Sophisticated. Unconventional,” Sharp thought.

Dickinson explained how the angular design was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright—the man who had presented him with his very first architectural award. The modular structure could also accommodate future expansion, as Sharp had asked.

“Peter,” Sharp said. “It’s perfect.”

A few months later, Dickinson died aged 35.

The task of turning the pencil sketch of the Four Seasons into a viable blueprint fell to Webb and Menkes, who formed their own firm out of the ruins of Dickinson Associates.

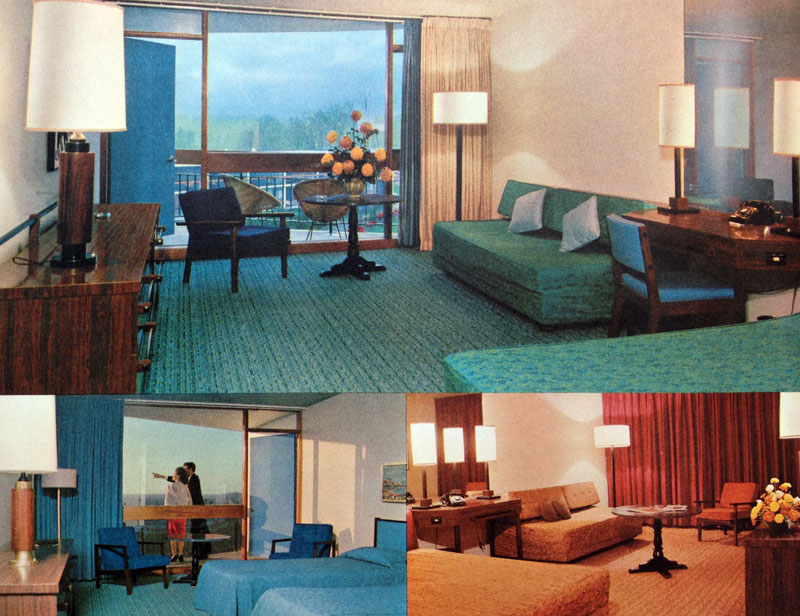

Isadore Sharp paid special attention to the design of the rooms at the Inn on the Park. Foam mattresses and self-cleaning, high-pressure “Act-o-Matic” showerheads were installed throughout. To reduce noise, plumbing was kept away from the concrete superstructure. City of Toronto Archives, Series 2, Fonds 607, File 164.

The finished product, which cost $3 million, opened in May, 1963. It was an instant success.

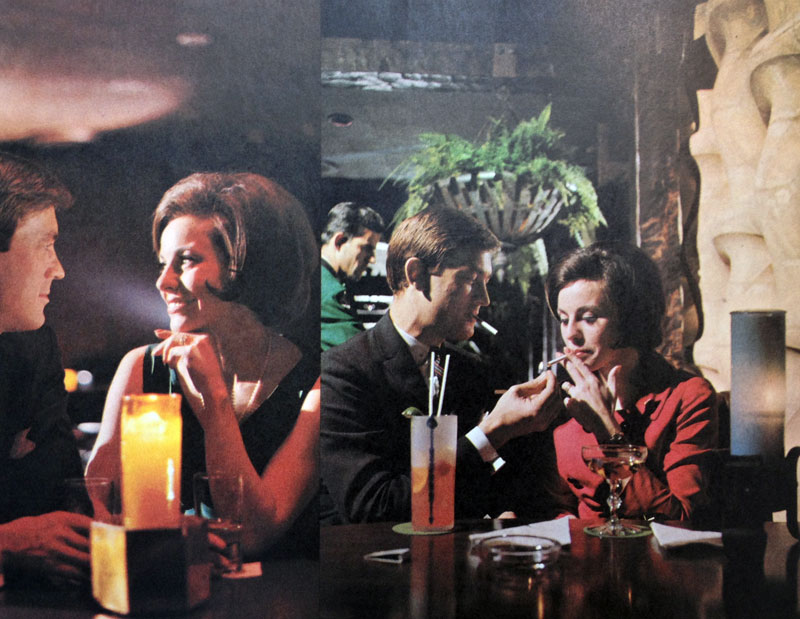

The complex contained a state-of-the-art health club run by fitness expert Lloyd Percival, a luxury 1,600-seat reception facility with bright red loop carpeting and oyster shell chandeliers, a pool, and a cocktail lounge—a first for North York, which had only lifted its ban on the sale of hard liquor earlier that year.

There were two dining rooms—the Vintage Room and the Buttery—and quite possibly the Toronto area’s first disco. At the Cafe Discotheque, waiters in white coats glided the dimly lit room, serving drinks. An in-house DJ spun tunes while imported New York City dance instructor Killer Joe Piro taught visitors how to do the Monkey, the Mashed Potato, the Mule, and the Mambo.

According to a wide-eyed Janurary, 1965 Globe and Mail article on the matter, the Cafe Discotheque was highly influential. Similar discos opened at the Steak Pit on Avenue and the Anndore Hotel on Charles. The Seaway Hotel soon had Musitek and Le Caboret the Live-o-Tek.

Not everyone was happy with the Inn on the Park’s pioneering dancehall. The Toronto Musicians Association blacklisted the hotel for using recorded music instead of live musicians. The Cafe did use a live trio to back up its DJ, but the TMA were still furious. “Live music for dancing is one of the most important sources of income for for professional musicians,” a spokesman said.

The disco didn’t last long, however. The dancers didn’t drink enough to make it economically viable and the space became another restaurant, Café de l’Auberge.

The Inn on the Park is credited with a couple of local firsts, including first disco and first cocktail lounge in North York. In his book, Isadore Sharp claimed to have pioneered the idea of smoking and non-smoking floors at the hotel. City of Toronto Archives, Series 2, Fonds 607, File 164.

One of the biggest factors in the Inn on the Park’s early success was the trend of internal tourism. Lured by the promise of swimming, sunbathing, golf, tennis, shuffleboard, and countless other activities, thousands of cottageless Torontonians vacationed in motor hotels a short drive from their homes in the 1960s.

“The phenomenon has changed the picture so radically that motor hotel proprietors now are planning campaigns to draw customers from the Metropolitan [Toronto] area year round,” the Globe and Mail reported.

Demand was so great the Inn on the Park was forced to briefly limit one-night bookings. To keep up, Four Seasons added 200 more rooms to the main block in 1965 and a 23-storey tower in 1971, but storm clouds were brewing.

The Inn on the Park began to hit hard times in the late 1970s. Internal tourism declined and a devastating fire in 1981 killed six people, including two children, and injured dozens more.

A coroners inquest found the blaze was likely started around 2:00 a.m. by a glowing cigarette in a janitor’s vacuum cleaner bag. The flames ignited nearby drapes and spread quickly to surrounding rooms, filling the ventilation system with thick toxic smoke.

The inquest recorded the slow and confused response of the hotel’s skeleton night crew as contributing factors in the deaths of Carol Charles, Candace Charles, Tricia Biega, Jamie Medina, Albert Thompson, and Cecil True. Four of the six died after becoming trapped in a stairwell.

Motor inns fell out fashion and the Inn on the Park became increasingly unloved and timeworn. With the decor faded and memories of the horrific fire still lingering, Four Seasons sold the complex to Holiday Inn.

The Inn on the Park lingered until 2005, when it closed for good and was mostly demolished to make way for a car dealership, despite the best efforts of preservationists.

We won’t see anything like it again.

The post The life and death of Peter Dickinson and The Inn on the Park appeared first on Spacing Toronto.