This post by Emma Heffernan, is part of Spacing’s partnership with the Toronto Cycling Think & Do Tank at the University of Toronto. Emma is a research assistant for both the Toronto Cycling Think & Do Tank and the Scarborough Cycles Project at the Toronto Centre for Active Transportation, a project of Clean Air Partnership. Scarborough Cycles is funded by the Metcalf Foundation’s Cycle City program, which aims to build a constituency and culture in support of cycling for transportation.

The line of middle aged men, balancing on bright green, step-through bikes, reach out their arms to the right. In turn, they each look over their right shoulder to check their blind spot. They then make the right turn. It is the parking lot of the Birchmount Bluffs Neighbourhood Centre in Scarborough, and these men have just received the bikes that they will use all summer. Free of charge.

“Let’s stop here!” The group leader is in his mid-20s with hair to his shoulders. He gestures towards the post and ring racks that stand in a straight line on the edge of the parking lot. The men each curl their arm in a square shape, their hands pointing down to the ground, to signal the stop. The group leader gets off his bike and pulls out his lock. “This is the safest way to lock your bike,” he explains, as he loops the lock through the metal frame and the bike wheel. “Always try to use the middle metal pole, because some thieves can cut through the sides.”

The four men pull out their locks, and begin locking their bikes to the posts. “Like this?” One asks. The group leader nods. One does not correctly loop his lock through the frame; he has mistakenly only locked his back wheel. This is a mistake that could cost him his bike in Toronto.

Unfortunately, I am not being dramatic – according to the Toronto Star over 18,000 bikes were reported stolen across the Toronto region between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2015. Having a bike stolen is upsetting for anyone, regardless of income. However, for low income individuals, the risk of having a bike stolen can mean the difference between justifying the upfront cost of investing in a bike – or not.

The expense associated with buying and maintaining a bike is a barrier to cycling for low-income individuals, according to a 2010 report from Portland that used focus groups with 49 people of color in low-income communities to understand their barriers to cycling. Though the report also notes that safety concerns and a lack of secure bicycle storage also influence whether low income individuals choose to bike, a majority – 60% of respondents – expressed concern about the cost of a bicycle.

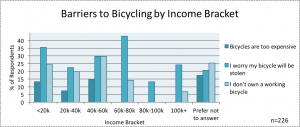

The cost of bicycles is not just a barrier to cycling in Portland. A 2016 survey conducted by University of Toronto researchers as part of the Scarborough Cycles project found those in lower incomes brackets were more likely to respond that financial concerns were part of the reason why they would choose not to bicycle, even if the weather was good. Specifically, 10-15% of those with incomes under $60,000 believe that bicycles are too expensive. Similarly, 20-30% of these individuals did not own a working bicycle. Although worry that the bicycle might be stolen was a concern regardless of income, those in lower income brackets were more likely to list this as a barrier to cycling than those in higher income brackets.

Figure 1: Barriers to Bicycling by Income Bracket, Source: Scarborough Cycles, 2016

Clearly, having less disposable income can impact whether individuals will choose to bicycle for transportation because of the associated costs associated as well as uncertainty about the benefits that they will derive. This makes sense: if I did not know that I would save money by riding my bicycle every day to work, I might not have invested in a bike when I moved to Toronto.

When my bike was stolen, if I had not had money saved, I would not have been able to afford a new bicycle. And, if I didn’t know how to repair my bike, it would be financially difficult to continually put cash down for someone else to fix it. In short, income matters, and it matters in ways that are affecting the composition of the cycling population in Toronto.

The cycling population in Toronto does not proportionally represent all income brackets. A 2009 Ipsos study found that individuals with incomes over $100,000/year were three times more likely to be utilitarian or recreational cyclists when compared to those who earn under $20,000/year. This indicates that the infrastructure related barriers that make many of us feel unsafe while cycling are not the only barriers that matter. If cycling is to increase among populations in Toronto not currently represented in the cycling community, there is a need for targeted and affordable programming.

In Toronto, programs such as Bike Pirates, Charlie’s Free Wheels, Bike Host and, yes, Scarborough Cycles make cycling more accessible for populations that otherwise might not have the opportunity to learn how to ride a bike safely in the city or how to economically maintain a bike. Given the ongoing cyclist income skew, these types of programs are integral to the promotion of a more inclusive cycling environment in Toronto rather than peripheral actions that supplement the ongoing call for more cycling infrastructure.

Please note: Summary data from the Scarborough Cycles Travel Survey will be published in a report in the Fall of 2016

The post Common Cents: The Impact of Income on Cycling appeared first on Spacing National.