Edited by Todd Gannon (Applied Research & Design Publishing, 2016)

No. 9 – Source Books in Architecture

Eric Owen Moss Architects/3585, the ninth in the Source Books for Architecture series, offers a unique look at the conceptual underpinnings and design processes of one of the most important architects working today through a comprehensive presentation of three schemes his office designed for a single site in the Hayden Tract in 1991.

- From the Foreword

There are not a lot of places on the global map that one can point to today as a locale for architectural experimentation, but Culver City, California is such a place. This is mostly due to architect Eric Owen Moss, whose critical examination of the synthesis between theory and practice has made him one of the most relevant voices in today’s current architectural discourse. A graduate of architecture schools at both Berkeley and Harvard, Eric began teaching at SCI-Arch in 1974, and was the school’s director from 2002 to 2015.

In Eric Owen Moss Architects/3585, edited by fellow architect Todd Gannon, the architect’s work is presented through both his ideas and his built projects. The latter half of the book is comprised of a large number of photos and technical drawings of three of his projects in Culver City, with the opening pages of the book consisting of several discussions with the architect on a variety of topics, selected by the book’s editor. These musings offer an insightful glimpse into the inner workings of the architect. His design philosophy and practice, taken together, to provide us with his critical view of the current state of architecture and the world.

His musings are far ranging in both tone and topic, starting with his recalling a march of 300,000 in the streets of San Francisco during his school years in Berkeley, a protest march against the Vietnam War that was to influence his understanding of the relationship between crowds and the city for the rest of his life. “That background contributed to the strategic positioning I’ve taken in architecture,” he claims, “Berkeley taught me there was something artificial about consensus, and something compromising about agreement.”

Another essay touches on his memory of a professor he had at Berkeley, Paffard Ketinge-Clay, who after graduating from the Architectural Association in London had worked on the Unite d’Habitation with Le Corbusier before coming to California. Finding himself a bit of a pariah, as he neither identified with the students or the faculty, he became an immediate role model for Moss. Besides designing the Student Union building for the campus, his influence was most evident in his support for Moss’ more unorthodox architectural narratives.

Moss also writes about the influence of a radical cosmologist he heard speak at Harvard in the 1970’s named Immanuel Velikovsky, whose theories refuted the entire trajectory of Western thought from Newton to Darwin. Moss refers to him as an advocate of catastrophism, and it is clear that his philosophy greatly influenced Moss’ own philosophy of the world. “I’m not saying he was correct; I’m not saying he was wrong. I’m saying even if he was wrong, he was right. He taught us to think independently; particularly in the way he evaluated the content of authorities in various disciplines.”

Much like Descartes in his Meditations, Moss speculates on the possible worlds that could’ve been, reflecting on pivotal moments in our history where humanity might have taken a radically different direction, and what the resultant outcome might have been. One of his more poignant observations comes in his imagining what could’ve been if Oppenheimer had chosen to utilize his atom-splitting science for a different purpose, to reach the moon or bottom of the ocean, to build cities or cure diseases instead of fashioning a weapon of mass destruction.

All of Moss’ influences are here—from Bob Dylan and T.S. Eliot, to Heraclitus and Friedrich Nietzsche—all of whom share with Velikovsky an often anti-establishment point of view, and who have clearly provided for Moss an inspiration for his philosophy and architecture in some way. Moss also shares his literary heroes such as Umberto Eco and Italo Calvino, along with his thoughts on global architecture, from that of ancient Rome and Greece to Mayan ball courts and the temples at Angkor Wat.

Furthermore, Moss writes about what it means to be a resident of LA: “One of Los Angeles’ useful qualities is its lack of moorings, its ephemerality. There is something substantive in this lack of durability. It is an adolescent city with all the implications of that term included: looking around, trying different models to see what might work, losing interest, going on to another prospect, and on and on.” In many ways, a young Canadian city such as Vancouver shares this adolescence with its southern counterpart, along with all the other cities along the western seaboard which oscillate between these two urban extremes.

There is some irony here, as well, in the presentation of his 2006 project for a wall on the Mexican border, certainly given the outcome of the recent American presidential race. Without a whit of tongue and cheek, Moss’ project imagined a 2000 mile long raised earth berm to run along the border, punctuated with crossing tunnels, lit from above with a forest of glass tubes. As commissioned by the New York Times Foreign Affairs Section to create a flashpoint for the topic, no one could’ve dreamed that a decade later something like it would become a prop for the presidential race.

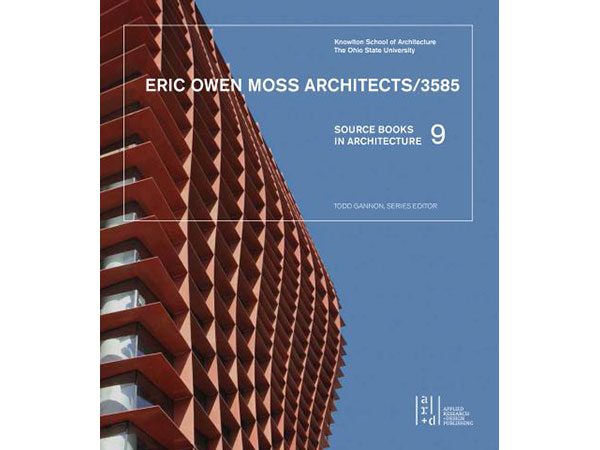

In the remainder of the book are three representative projects, all of which are located at 3585 Hayden Avenue in Culver City, to which the book’s title refers. Beginning in 1991 and extending all the way to the present day, Moss and his office designed and re-designed a number of tower studies over twenty five years, beginning with the Hayden Tower in 1991, progressing to a study for Ten Towers for the site, and finally being realized in two built towers called the Waffle and Cactus Tower, respectfully.

The tabula rasa nature of the post-industrial site provided Moss and his office with the perfect point of departure upon which to root his architectural pedagogy: “The question, for both theoretical and practical reasons is always what to erase, what to keep, and why.”

The two towers which have taken shape to date are simultaneously playful and serious—the parametric patterning of both the Waffle Tower and its twin the Cactus Tower balanced by the austere structural frame from which it is formed, taking the appearance of a vertical version of Jurgen Mayer’s Metropol Parasol in Seville.

All three schemes are presented outright and then are followed by a Q&A between Moss and Todd Gannon, the book’s editor, each project accompanied by a wealth of sketches, drawings, models, renderings and working drawings, as well as an extensive photographic record of each building’s construction.

Eric Owen Moss/3585 is a thoughtful and thorough monograph of this provocative architect‘s work, and continues the high standard of the Source Books which also features in its series Morphosis, Steven Holl, and the late Zaha Hadid to name only a few. With much of the material coming from conversations between Moss and students at the Knowlton School of Architecture in 2011-12, along with a 2015 interview with the book’s editor, this book offers an insightful glimpse into one of architecture’s most prodigious advocates, and will prove both an invaluable source of inspiration and cultural reference for both the architecture student and professional alike.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and writer.

The post Book Review: Eric Owen Moss Architects/3585 appeared first on Spacing National.