On June 3, 1971, there was a party on downtown Yonge Street. Around 8pm, following the news that Ontario Premier Bill Davis had cancelled the Spadina Expressway, jubilant opponents of the project gathered to celebrate. Guitars and banners in hand, they gravitated to Yonge: always a meeting place, but particularly appropriate that night. Just a few days earlier, four blocks of the street had been closed to car traffic to create Toronto’s first pedestrian-only street. For the Stop Spadina activists the closure had a powerful symbolic dimension. One of their slogans — repeated by Bill Davis in his press conference that afternoon — was that “the streets belong to the people.” The Yonge Street pedestrian mall, where four lanes of traffic were replaced by milling crowds, trees, and beer gardens, seemed to perfectly embody those words.

For four summers in the early 1970s, Torontonians and visitors congregated on a car-free Yonge Street to shop, stroll, and enjoy the spectacle of downtown life. Expressway opponents were by no means the only people who had big hopes — or fears — for the future of the mall. Because the idea was new, because it was tied in with so many of the concerns of the age, and because it happened on Toronto’s main drag, the project was both popular and controversial. Today, amid growing interest in making Toronto streets more people-friendly — Open Streets is just one example — it’s worth looking back at the pedestrianization experiment that started it all.

Planning for people

Flâneur-friendly shopping streets and piazzas have been a part of urban life for centuries, but the pedestrian mall as we know it in North America is a product of the automobile age. In the post-World War II era, massive suburban expansion and increased (auto)mobility seemed to threaten the very existence of downtown as a place, let alone as the place to go for shopping or entertainment. Old-style retail strips like Yonge south of Bloor — often referred to nostalgically as “Toronto’s Main Street” — were losing ground to more convenient suburban alternatives. In that context, pedestrian malls were seen as a way to beat the ’burbs at their own game, moving the successful shopping mall model — attractive, pedestrian-only areas with ample nearby parking — into the heart of the city. It is no coincidence that one of the best-known designers of pedestrian zones, Victor Gruen, was also widely hailed as the father of the modern shopping centre. By 1970, 30 cities in Canada and the United States — including Kalamazoo (1959) and Ottawa (1967) — had closed downtown thoroughfares to cars, dressing them up with street furniture, trees, and other improvements. By 1978, that number had grown to nearly 100.

The same drive to revitalize sparked Toronto’s interest in pedestrianization. For years, independent retailers, especially those on Yonge Street, had been asking the city to do something to keep people downtown. There was a widespread sense in Toronto that while office construction was booming, the area was losing its attraction as a people place. City planners were sympathetic, and agreed that Yonge had all the attributes necessary to host a pedestrian mall: plenty of foot traffic, a range of shops and entertainment options, and a subway running its length. But their 1960s proposals for pedestrian zones — not just on Yonge, but also for Kensington Market, the Elizabeth Street Chinatown, and the bohemian Village on Gerrard — gained little support in city council or, in fact, in the neighbourhoods they were intended to protect.

That changed at the close of the decade, as a surge in community activism ushered in a period of change at City Hall. A growing number of Torontonians were pushing back against projects, like the Spadina Expressway, that they felt put growth ahead of community interests and the environment. In the summer of 1970, pioneering green advocacy group Pollution Probe proposed a bold (and almost successful) scheme to close Bay Street for a week to raise awareness of air pollution. Suddenly, it seemed like everyone was talking about planning for people and limiting the effects of the car on the city; in that context, pedestrian malls stopped being just another low-priority planning item and started looking like a chance for the city to embrace what one councillor called “the new thinking of the ’70s.” Working in partnership with local merchants, Metro Toronto, and the province, the City planned a week-long experimental closure that, if successful, could be the model for a permanent mall.

A miracle on Yonge Street?

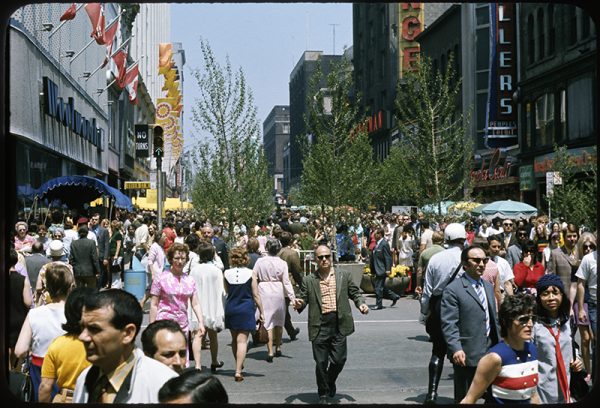

Overnight, the four pedestrianized blocks of Yonge Street — from Adelaide to Albert (just south of where Shuter St. meets Yonge today) — became Toronto’s most popular public space. Tens of thousands of people visited each day to stroll and window-shop; in the evenings they took in the entertainment program laid on by area businesses (puppet shows for the kids, rockabilly and square dancing for the adults). Perhaps the most popular attractions were two licensed outdoor cafés — a Toronto first — where long lines of people waited patiently for a seat and a chance to watch the crowds with a drink in hand (“It’s just like Paris!” exclaimed one patron). Everything about the mall suggested a suspension of the conditions of ordinary life: strolling was encouraged and impromptu concerts sprung up on street corners. And in the most un-Toronto way, you could smile at complete strangers or sip a beer outdoors.

By the end of the week, ecstatic observers were calling the mall a miracle, and speculating that its appearance was the final nail in the coffin for the buttoned-down Toronto the Dreary, what architect John C. Parkin called a “city of corridors without a living room.” Had the city at last found its groove? Local political reformers, jaded by years of fighting City Hall, were delighted to discover a planning initiative they could embrace. But there was more to it than that. In the 1960s and 1970s, Torontonians across the political spectrum were eager to see the city shed its provincial image and take its place alongside other world-class cities: a safer, more harmonious version of New York. Certainly that was how the city sold itself to growing numbers of American tourists. The Yonge Street pedestrian mall seemed a perfect fit for that vision of Toronto, complementing more grandiose projects like New City Hall with its human-scaled, Main Street feel.

Within a few days of Yonge’s return to normality, petitions calling for more street closures (and permanent ones) were making the rounds, and business owners further north in the Gerrard/Dundas entertainment area — “the Strip” — were forming plans for their own mall. They were well aware that the first time around nearly every business fronting on the pedestrian mall had reported a boost in sales (with the notable exception of Simpson’s department store, opposed to the idea from the start because it would interfere with vehicle access to their store). Why shouldn’t the Strip, which despite the crowds had its own woes — things like property speculation, flagging sales, and the mushrooming of adult entertainment businesses — get in on the action? As the Yonge Street closures grew in length — six weeks in the summer of 1972, 12 in 1973 — they also expanded north, giving the mall a more exciting (and somewhat seedier) feel.

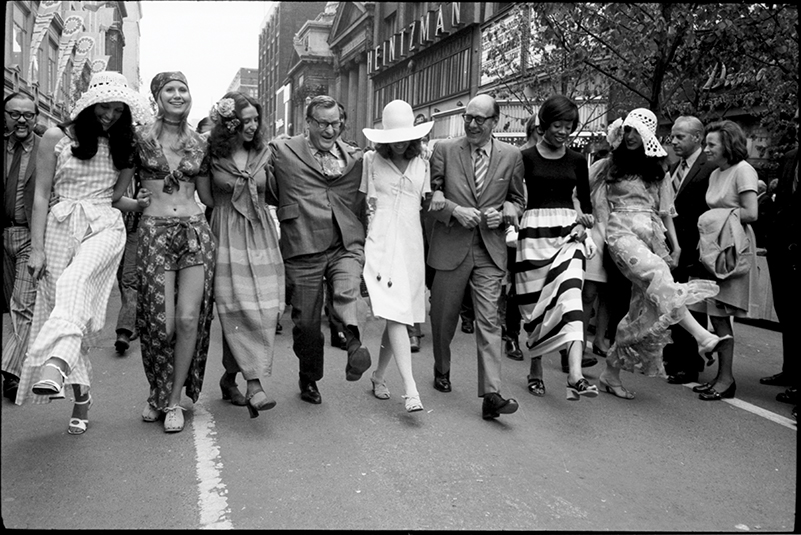

William Archer and federal Conservative leader Robert Stanfield parade with models on the mall. David Davies/Toronto Telegram, 1971. Clara Thomas Archives

New spaces, new uses

Removing cars from Yonge each year created a vast new public space with its own particular human ecology: Jane Jacobs’ “ballet of the sidewalk” in its most concentrated form. The crowds that thronged the street grew and shrank depending on the hour and the weather: office workers and shoppers dominated during weekday lunch hours, while Friday and Saturday nights attracted boisterous crowds of youth. There was no better place in Toronto to vend, busk, beg for change, or proclaim the truth at the top of one’s lungs. By day, Yonge’s iconic shoeshine boys did a roaring trade; by night, a growing number of prostitutes discreetly mingled with crowds on the Strip.

The mall also showed its potential as a political stage. On opening day in May 1971, Pollution Probe stole the show by organizing a parade of hundreds of bell-ringing cyclists, intended to raise awareness of air pollution and transportation alternatives. Countercultural enclave Rochdale College briefly took over the street with its own brand of cultural protest, an irreverent convocation ceremony featuring hundreds of kazoos. And politicians at all levels of government, from mall organizers like Alderman William Archer to federal leader of the opposition Robert Stanfield, took time to bolster their political fortunes with meet-and-greets on the mall.

Problems and solutions

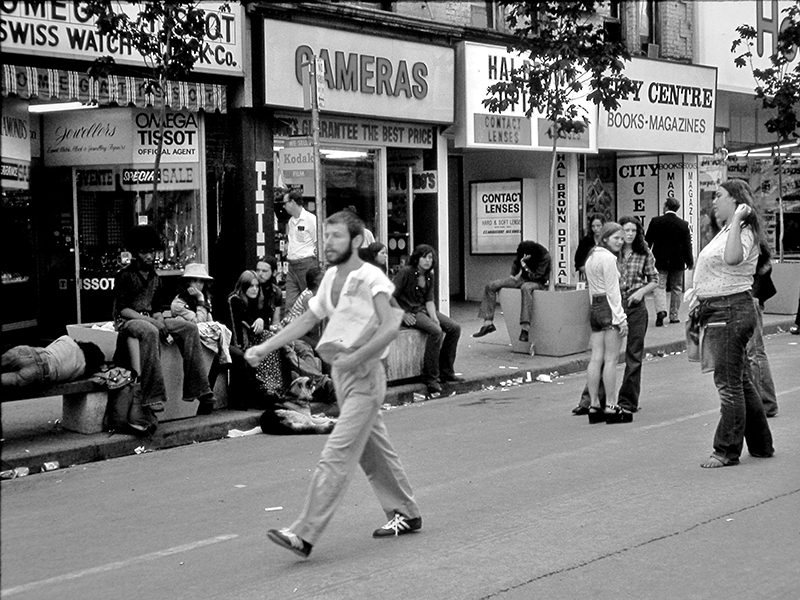

In short, the pedestrian mall was everything downtown Yonge Street was — crowded, commercialized, and full of life — only more so. Inevitably, this created conflicts, and by 1973 the project’s public image was beginning to lose its lustre. Some merchants were frustrated by unlicensed vendors cutting into their business; a growing number felt the mall was really only benefiting taverns and restaurants. Meanwhile, members of the public complained of explicit advertising for body rub parlours and strip shows, aggressive panhandling, and groups of directionless, probably degenerate, “hippies” and other non-conformist youth. A couple from Ohio wrote to newly-elected Mayor David Crombie to express their shock at being victims of a con game (the old bait-and-switch, an annual attraction on the mall) in such a safe, friendly city.

Mall organizers tried to address these concerns with design changes — for example, creating a designated area for street vendors, and removing a grassy lawn where the so-called hippies were congregating — and by asking for more patrols by police and licensing inspectors. But their efforts were undermined by the police brass, who viewed the event as a waste of their officers’ time. In a 1973 report, Chief Harold Adamson called the mall “a haven for missing juveniles, drug users, drug sellers, and drunks,” and presented the public with a laundry list of hundreds of arrests made during (and, he implied, because of) that summer’s closure: 173 for drugs, 475 for drunk and disorderly conduct, and so on. A damning report, or so it seemed; in fact Adamson’s numbers are roughly comparable to arrest rates in subsequent, non-mall years, suggesting that other factors — new drug laws, demographics, the Strip’s concentration of taverns — were at work. Yet in a period of anxiety about youth misbehaviour, the association between the Yonge Street Mall and crime stuck, particularly after a 1974 York County Grand Jury called it “a blot on Toronto” and recommended the experiment be discontinued.

As the mall grew from a week-long festival to something resembling a permanent closure, it also drew the ire of transportation planners. Despite organizers’ valiant efforts to make the mall work within Metro Toronto’s overall traffic plan — opening cross-streets to east-west traffic, diverting buses, deploying dozens of traffic police — officials like Commissioner of Roads and Traffic Sam Cass still viewed the mall primarily as an obstacle, not just to traffic, but to their vision of a more efficient city. Behind Cass’s yearly predictions of “chaotic traffic jams” and other dire consequences of continued closure were long-frustrated plans for downtown Yonge Street to be converted into a one-way arterial for commuter traffic.

The morning after on the mall, 1972. Bob Whalen

An end — and a beginning

The growing debate over the mall’s impact on Yonge Street’s decline — was it a solution, or part of the problem? — meant that, when it was abruptly removed to help cope with the 1974 TTC strike, there was no immediate move to have it reinstalled. That year, a report contracted by the City recommended a permanent mall; but while several proposals were drawn up, including a sensible 1977 compromise option that preserved two lanes for traffic, it proved impossible to get all the various stakeholders fully onside. Similar patterns were playing out in other cities, too; it was becoming clear that small-scale pedestrian improvements weren’t the panacea for downtown problems they had appeared to be a decade earlier.

As the years passed, the heady days of the early malls started to seem like just another 1960s pipe dream. Toronto did get a mall on Yonge in 1977 — the privately-owned, air-conditioned shopping mecca of the Eaton Centre — and it was popular, although no one thought it felt like Paris, or that it would transform city life.

Even if it never lived up to the futures imagined by its most ardent supporters, the Yonge Street Mall was by no means a failure. It demonstrated just how much Torontonians could appreciate new public space, street entertainment, and a break from the usual strict separation of uses. Over the past 40 years, dozens of street festivals similar to the 1971 Yonge mall — if not the more ambitious later ones — have become an integral part of Toronto summers. Some things haven’t changed: drivers and the police still gripe, and sometimes people don’t know how to behave. But on the whole, we’ve assimilated these little shake-ups of the urban order into our vision of city life, and in that respect, the Yonge pedestrian mall of the 1970s was a beginning, not an end.

This story originally appeared in Spacing‘s Winter 2016 issue. Daniel Ross is an urban historian and an editor of ActiveHistory.ca.

This story originally appeared in Spacing‘s Winter 2016 issue. Daniel Ross is an urban historian and an editor of ActiveHistory.ca.

The post Yonge Street Mall: The fun and failure of pedestrianizing Toronto’s iconic strip during the 1970s appeared first on Spacing Toronto.