Ten years ago, as a grad student researching the history of Toronto’s waterfront, I came across a study, published in 1977, that could very well have been written today: “Should the Island be an Airport?”

The report, I came to learn, was produced by a long-lived, but largely forgotten, citizens group known as the Bureau of Municipal Research.

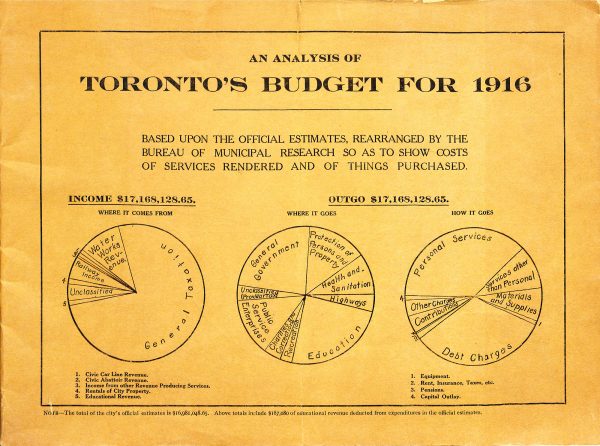

The Bureau was established in 1914, as the Toronto Daily Star reported at the time, as a centre of “general municipal intelligence.” Its mission and motto was to produce “better government through research,” and for seventy years that’s what it did, publishing over 800 research bulletins and reports on more than a hundred different topics, before closing its doors in 1983.

The more boxes I cracked open, the more Bureau reports turned up. Almost all, it seemed, hit on today’s hot-button issues.

“There is no doubt,” concludes one report, “that something drastic needs to be done about rapid transit.” The year? 1945.

Housing, taxes, poverty, sprawl, garbage, libraries, road tolls, even mental health — the Bureau covered it all. Many of the questions it raised, in some cases a century ago, still don’t have good answers.

“If proportional representation secured more representative government,” asked the Bureau back in 1919, “would it not be time well spent?”

“Why the apathy in local elections?” (1957)

“Municipal services: Who should pay?” (1980)

Before I knew it, I had lost track of what was then, and what is now.

So I did what any good historical researcher working in the late aughts would do: I pulled out my point-and-shoot digital camera (remember those?) and started “scanning.” Every time I came across another Bureau report, I’d take a photo.

A 1977 study of proposals to reorganize Toronto’s metropolitan government by Anne Golden, now chair of Ryerson’s City Building Institute. Click.

A 1971 report on the impact of the Ontario Municipal Board by Susan Schiller (née Fish), now a member of the Local Planning Appeals Tribunal. Click.

Bit by bit, I began building my own little archival collection. Turns out, I wasn’t alone. In 2011, electoral reform activist Dave Meslin organized an unofficial “BMR day” at the City of Toronto Archives with the same idea. A handful of volunteers chipped in, but there was too much material to sort through.

The Bureau was forced to close in 1983 for lack of money, not output.

Originally funded strictly by public-spirited individuals, the Bureau eventually came to depend on donations from business and labour groups, contributions from academic institutions, and, in the latter years, government grants. When those grants dried up, in the late 1970s, the Bureau’s fate was sealed, its work transferred to the archives.

Inspired by these efforts, I set myself a new goal: to digitize the Bureau’s entire research library.

The work began in earnest in 2014, what would have been the Bureau’s 100th anniversary. With the help of six U of T students, from the School of Public Policy and Governance as well as the departments of history, information studies, and computer science, we began the laborious process of systematically digitizing, coding, and cataloguing all 830 Bureau publications in the archive’s collection.

Four years and hundreds of hours later, the Bureau of Municipal Research digital archive is now complete, available for all to explore at www.bomr.ca.

Whether you are a city nerd, a history buff, a policy wonk, or just curious, it’s all there waiting for you to immerse yourself in over a century of Toronto heritage.

You’ll find summaries of the Bureau’s work on popular topics such as housing, transit, education, waterfront redevelopment, and the environment. You can also browse the collection by theme, or search the catalogue for a particular title.

My hope is that the Bureau becomes a resource for writers, researchers, educators, and everyday citizens to learn more about this great city, and importantly, the countless public policy decisions that have contributed to its making.

The collection is a reminder that many of today’s most pressing urban challenges — and indeed, most of their solutions — have all been studied before.

A few years ago, Spacing contributor Pamela Robinson mused about the benefits of reviving the Bureau as a tool for civic engagement and innovation. I believe the Bureau’s potential stretches even further.

In its heyday, the Bureau was respected as “a constructive force for civic betterment.” It championed the public’s right to know, demanded fairness and honesty from local leaders, and produced the kind of high-quality research necessary to keep government accountable.

It was, at its core, a guardian of good governance. For the sake of all Torontonians, its legacy must live on.

Gabriel Eidelman (@GabrielEidelman) is director of the Urban Policy Lab, a teaching and research hub at the University of Toronto’s School of Public Policy and Governance, and creator of the Bureau of Municipal Research digital archive. Learn more about the Bureau’s history, and explore the complete digitized collection, at www.bomr.ca.

The post Why I revived the Bureau of Municipal Research appeared first on Spacing Toronto.