When we plan for our transportation future, whether we’re talking at the municipal, regional or provincial level, there’s an elephant in the room. Even the most serious plans avoid it. If we take climate changes as seriously as we should, we must talk about the one thing we do not want to talk about: the need to reduce car use.

I teach an introductory human geography course. Every year, when I lecture on the politics of climate change, I include a slide of headlines: “faster than expected,” “worse than predicted.” Every year, I update the slide with more headlines. There are always more headlines.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change just put out its latest report. Its expert advice is that we need to keep the planet from warming more than 1.5 degrees over pre-industrial levels. We’re already 1 degree over. It’s possible to achieve this, but we need to take major, comprehensive action by 2030, or the cumulative effects of previous warming will push us over the line.

Basically, this report is a bucket of ice water to the face. It tells us we’ve got 12 years, max, to prevent a bad situation from becoming catastrophic. It seems small, but even the difference between 1.5 degrees and 2 degrees of warming is significant.

If we keep doing what we’re doing, we’re currently on track for 3.5 to 4 degrees of warming.

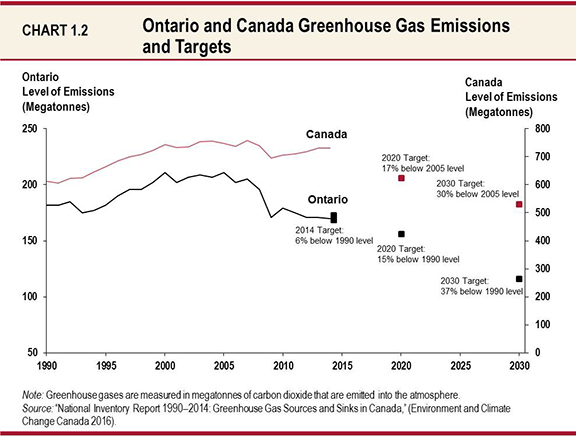

Canada is shamefully behind on its commitments to reduce emissions. The only declines we’ve seen since the 1990s are the result of Ontario’s closure of coal plants, and the recession of 2008-09. Here’s a chart from the Provincial Government’s Fall 2016 Economic Outlook. Ontario has made some progress; Canada as a whole is moving in the wrong direction.

By failing to significantly reduce our CO2 emissions, we’re setting in motion complex chains of reaction that cannot be easily undone. Some cannot be undone at all.

The planet’s air is warming, and so are the oceans. It is the oceans that absorb the vast majority of CO2, and as they do, they also become more acidic. This affects not only the ocean as a habitat, but the entire hydrosphere – the relationships among rivers, lakes, oceans, air, soil moisture, clouds, rain, snow, glaciers, sea ice. There is no place to live outside of this.

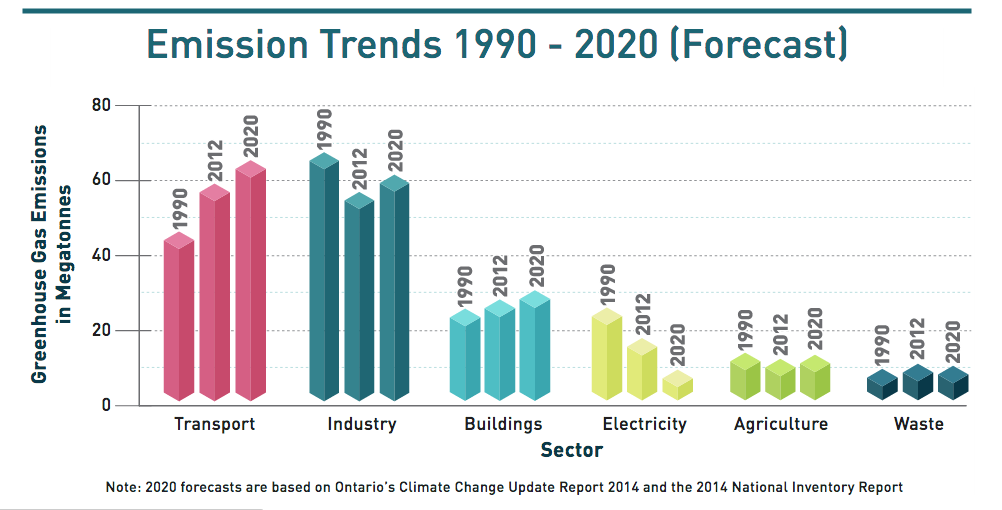

Transportation is a significant contributor to CO2 emissions: one-third of Ontario’s. As you can see from this chart from the Province’s Five Year Climate Change Action Plan 2016-2020 [pdf] (p. 7), it is also the only major sector where emissions have continued to rise.

Private automobile use is a leading contributor within that sector. The same Action Plan notes that “Greenhouse gas pollution from cars account for more emissions than from industries like iron, steel, cement and chemicals combined.” (p. 20) In addition, cars generate other forms of pollution that has been associated with many negative health outcomes: increased asthma, heart and lung disease, diabetes, and birth defects.

Despite this, our transportation and climate change plans rarely include any serious commitment to reduce automobile use. It is not enough to encourage transit use or active transportation. We must actively try to get cars off the road.

We need to set ambitious targets and make a concrete plan to meet them. I would propose cutting private-car-miles-travelled in the GTHA by 50% within 10 years.

The 2017 Growth Plan [pdf] for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, from the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, calls for municipalities to develop specific policies with specific actions, which are to include “reducing dependence on the automobile” (p. 52). There are no actual targets.

The provincial Action Plan talks about lower-carbon fuels and vehicles, but not reducing private cars or their use.

The province’s 25-year regional transportation plan from Metrolinx recognizes the need to “prepare for an uncertain future” (see Strategy 5 of Metrolinx’ 2041 regional plan [pdf]). One aspect (the third in a list of six) is to “address climate resiliency of the transportation system.” Most of the concerns are about the potential costs to the transportation system from severe weather events, like flooding.

The Metrolinx plan anticipates increased travel throughout the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, and hopes to divert some of it to transit, but there are few specific goals for increased ridership. If the ENTIRE plan is implemented, transit mode share in the region is only projected to rise from 14.2% to 14.7%. In 25 years. TWENTY-FIVE YEARS.

Perhaps more significantly, there are no targets for reduced use of private vehicles. Because there is no serious plan to reduce cars, even with a fully implemented GTHA transportation plan, kilometres of congested driving in the region are still expected to more than double by 2041, from 3.7 million to 8.1 million.

Last but not least, Toronto’s 2017 TransformTO [pdf] plan also lacks hard targets for reducing car use. Looking ahead to 2050, its goal is that all forms of transport use low or zero-carbon energy sources, and that active transportation account for 75% of trips in city less than 5 km.

That sounds pretty good, but according to the 2016 Census commuter data, the City is already at about 65% for those trips. The longer the trip, the more likely people are to drive.

For those traveling 5 to 10 km, the share of people walking, cycling or taking transit drops to 50%. Distances under 10 km in a city should not require a car.

By focussing on short distances, the plan hopes to reduce car trips by increasing cycling and walking dramatically (from 12% to 45%!). The actions in TransformTO that might get people out of cars are limited: “explore road pricing” and “significant active transportation infrastructure investment.”

Similar to the Metrolinx plan, TransformTO only projects a 1-point increase in transit use (22% to 23%).

In provincial, regional and local plans, we are relying on low-carbon energy sources for vehicles to reduce emissions, rather than reduced use of cars themselves. It’s not enough.

We need ambitious and specific goals. We need targets for reductions in car use, reductions in parking spaces, reductions in lanes for private cars with one occupant.

Easier said than done. A reduction in car usage has to be doable. It is not reasonably nor realistic to expect people to make their lives harder.

Think about what you need in your neighbourhood to make it better to walk, cycle or take transit instead of driving. And then demand that governments make it happen.

The provincial and municipal planning documents are full of good ideas and good intentions. They include everything from sidewalks to wayfinding to land use planning, the need to shrink the distances people travel for daily needs, the need for frequent and reliable transit service.

But that’s not enough. We also need to stop widening roads. We need to expand pedestrian spaces, cycling lanes and transit infrastructure, and shrink the space given to private cars.

This is going to cost money. A lot of it. But don’t kid yourself that the status quo isn’t going to cost all of us much more—in money, health, political stability, and lives lost. These investments will be money well spent.

As a bonus, we’ll not just be creating a cleaner environment – we’ll be building better places for people to live, stronger communities, and safer spaces.

Our goal must be more people walking, cycling and taking transit, AND fewer—far fewer—cars on the road.

We need to have clear targets, to measure our progress, and re-double our efforts when we fall short. We can’t reduce our emissions significantly without reducing the use of private cars. And if we don’t reduce our emissions now, we’re in big trouble, even in a safe place like Toronto.

Patricia Burke Wood is a geography professor at York University and a co-founder of its City Institute.

The post We need to talk about cars appeared first on Spacing Toronto.