As readers of my column know, I am an avid promoter of site-specific artworks, and I’m not alone. The kinds of conversations we are having today about site-specificity first started with the rise of the minimalist art movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Since then, a slew of literature has been written on the subject, with the term itself becoming a mawkishly overused buzz word.

While site-specific artworks are generally understood as works of art that reflect the identity and characteristics of a given place, the particulars of what this definition actually means is up for debate. We may assume that qualities like geography, architecture, and commerce constitute some of the integral characteristics of a site, but these features can fluctuate in importance and take on different meanings for different people.

The passage of time can also drastically change the meaning of a certain place and the associating characteristics that define it. Can we, for example, consider an artwork’s representation of history to be site-specific if its portrayal of events runs counter to a new perception or evaluation of the past?

Furthermore, will the site-specific art of “now” have any bearing on its locale in 50 or 100 years? If not, does that work still constitute a site-specific artwork by virtue of its already existing in that space? To make matters even more confusing, what even counts as a “site”? Is it physical or imagined? If it’s the latter, is a site culturally constructed or purely subjective? My queries could go on and on…

In her new work, Deep Times > Portals > Particles > & Pulls, collage artist Maggie Groat has addressed a number of the ambiguities regarding site-specificity and the philosophically fraught questions surrounding it. Commissioned by Infrastructure Ontario, Groat’s piece is installed at the construction site of Toronto’s new courthouse at 10 Armoury Street. In preparation for the construction, Infrastructure Ontario unearthed a wealth of archeological artifacts from when the site was known as “The Ward,” a now forgotten Toronto neighbourhood that was once home to impoverished Canadian immigrants from countries like Ireland, pre-Civil War America, China, Russia and Italy.

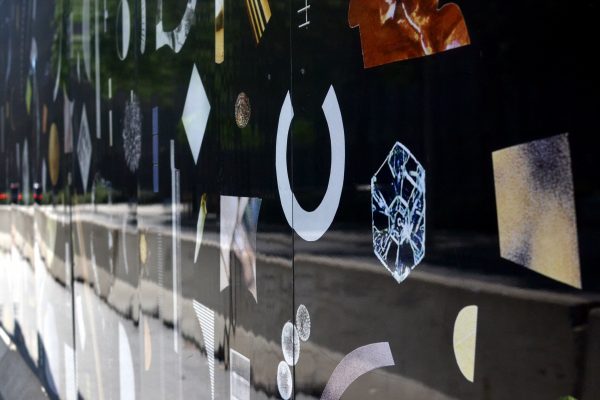

With a black background that evokes a sense of the cosmos, Groat’s mural reveals a myriad of images inspired by her time with the archeological findings and the history of the site. These objects, however, are not what you would necessarily expect to see. Most of the images are fragments of photographs or close-ups on the margins of images. The cut-and-paste effect highlights the juxtaposition between objects while simultaneously evoking connections between them.

When seen individually, the figures appear as if placed at random, mirroring the disparate assortment of objects uncovered when the artifacts were first found. But when viewed together, Groat’s fragments give the impression of being assembled with the utmost precision, creating a strange sense of harmony within the piece. The collage is akin to found poetry — a kind of writing where supposedly random words and phrases (or in this case images) are brought together to create a new meaning through re-contextualization.

Distributed throughout the collage are what Groat describes as “imperfect portals” — large, broken circles that act as potential “entry points” into the piece’s non-linear flow. While various objects at first appear to be rotating around these pivotal openings, the orbits slowly break apart as the images move further and further away from the spurious center (hence the phrase “portals, particles and pulls” in the work’s title). For Groat, this repetition of shifting circles creates “a sense of momentum, of folding and unfolding, [evoking the] imperfect symmetry of history, past and present.”

Groat isn’t interested in providing a taxonomic description of the collage’s images and the way in which they connect to the archeological findings. Instead, she would rather let people interpret or even create their own connections. One of the reasons for this is that Groat’s archival-based collage looks to the future just as much as it does to the past. Instead of thinking about her piece in terms of centuries, Groat has conceptualized it in terms of millennia, using the artwork as a platform to conjecture about the potential futures of the site. These imagined futures not only create an opening for new histories, but also foster a novel sense of place in the present.

Groat’s piece, then, collapses all of our contradictory definitions about site-specificity and condenses them into one work, thereby both validating and undermining our preconceived notions. By hypothesizing possible pasts, presents, and futures, Deep Times helps the viewer to envision various potentialities for the site, and in doing so makes those speculations a feature of the place itself. Rather than creating a site-specific artwork that seeks to bring forth the current, manifest characteristics of an area, Groat has instead created a work of art that is site-specific based on conjectures of what the site could be for the viewer.

Because of her focus on potentiality, Groat’s site is not fixed but is instead in a state of constant flux. While some artists argue that a site-specific work is inextricably linked to the location where it resides, Groat’s collage allows for a more fluid, transient notion of site-specificity. This point is further emphasized by the fact that Groat’s piece is only up for three years — the time during which the courthouse is under construction.

Some people may find this treatment of site-specificity too broad. If a site-specific artwork can comment on the potentialities of a place rather than the locale’s present realities, then couldn’t anything be considered site-specific?

The answer is “yes,” but that is because anything can be site-specific. What was once considered unrelated to a site can eventually become an integral feature, just as what was once considered site-specific can eventually become anachronistic. This flexible definition is also in keeping with the layered and multifaceted nature of sites, especially those in cities.

Deep Times > Portals > Particles > & Pulls succeeds in actualizing these contradictions while still creating a work that contributes to place-making. Groat’s collage not only allows us to break free from the dated, rigid notions of site-specificity, but also enables us to construct new places and identities.

What possible futures do you see?

Sarah Ratzlaff is Spacing’s public art critic. Follow her on twitter at @ratzlaff_sarah

The post Time for public art: the New Toronto Courthouse construction site mural appeared first on Spacing Toronto.