Natasha Henry is a 2018 Vanier Scholar completing a PhD in History at York University on the enslavement of Africans in early Ontario. She is the president of the Ontario Black History Society.

There are differing views on official apologies. Some believe an apology is an important first step in reconciliation and a key part of redress and remembrance. Others believe that apologies are hollow without concrete policy actions and funding. Then there is another group that doesn’t care for empty platitudes and are only concerned with actionable steps that move the agenda of justice forward.

Given how the Government of Canada has issued apologies to other communities that were harmed in the past, the hesitation and refusal by Ottawa to make the recommended and demanded apology further illustrates how Black Canadians are not valued.

Last week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was asked when or if he would apologize for Canada’s history of the enslavement of African people, as recommended in the 2017 United Nations Report of the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent on its Mission to Canada. His non-answer — “we will continue to work with the black community on the things we need to do” — is a common deflection by government leaders. These ‘duck and delay’ tactics are indicative of the state’s persistent historic disregard for Black life, and mirrors how Canadians steadfastly refuse to acknowledge racial slavery as part of their colonial origins, national consciousness and legacies within society and institutions.

The 17th, 18th, and 19th century empire building and colonizing project of the French and British regimes in the New World were rife with settler colonial violence that involved the theft of Indigenous lands and the exploitation of the labour of indigenous Africans through racial slavery. This was the origin of the territories we now call Canada.

African men, women, and children had been enslaved in colonial Canada since the early 17th century, first under French rule in northern New France (what’s now Atlantic Canada, Newfoundland, Québec, Ontario and southward to Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley).

The earliest record of African enslavement in colonial Canada was the sale of a young boy christened Olivier LeJeune in 1629. Indigenous people were the first enslaved racial group and formed the majority until the British victory in the Seven Years’ War in 1763. Following the secession of New France to Great Britain, Québec historian Marcel Trudel determined that out of approximately 4,200 slaves in New France and later British-colonized Quebec, about 2,700 were Indigenous people and approximately 1,450 were African people.

The security of the right to hold slaves was an important matter that received its own clause in the 1760 Articles of Capitulation, signed at the surrender of Montréal. Article XLVII confirmed that both African and Indigenous slaves would remain in their condition after the transition of power.

The Negroes and panis of both sexes shall remain, in their quality of slaves, in the possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong; they shall be at liberty to keep them in their service in the colony, or to sell them; and they may also continue to bring them up in the Roman Religion…

The change in colonial control resulted in a shift in the demographics of those held in chattel slavery and saw a dramatic increase in the number of enslaved African people after the influx of Loyalist refugees into British North America following the American Revolution (1775 – 1783).

Scores of Loyalists brought approximately 3,000 Africans they had enslaved in the Thirteen Colonies with them to their new settlements. Around 3,000 enslaved African men, women and children were brought into British North America by Loyalists during the relocation. It is estimated that by the 1790s, the number of enslaved Black people in the Maritimes ranged from 1,200 to 2,000. There were about 300 in Lower Canada (Québec) and 500 to 700 in Upper Canada (Ontario).

These numbers were boosted by the enslaved Africans captured as spoils of war by Indigenous allies from raids conducted in the United States and sold or gifted to their Loyalist comrades when they transported them north. The Brant siblings, Joseph and Mary (aka Molly), both enslaved Africans. Joseph held upwards of 40 slaves between his two properties in Burlington and Brantford, while Mary brought two women and one man to settle with her and her family in Kingston.

Enslaved Africans were highly valued. In the midst of the hardships of exile, some Loyalists held on to their slaves even though they had no money to purchase food for them. According to a 1784 letter in the Haldimand Collection at Library and Archives Canada, several Loyalists asked the British military for assistance with provisions for their slaves, noting, “to dispose of them would be adding to their Distress, as they were the only means of cultivating their lands they have when they go upon them.”

“A Pilot steering down the rapids of the St. Lawrence River” by Henry Byam Martin, 1832. Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1981-42-12

As was customary, white colonists used the free labour of enslaved Africans to help in the development of the new territories. However, the efforts of white settlers to import large pools of enslaved labour was hampered by political and environmental factors, including maritime conflicts between European powers. Enslavement in British North America therefore was smaller in scale and primarily domestic and agrarian.

Still, the enslavement of African people was prevalent in colonial Canada. Political and social elites, former military officers and soldiers, fur traders, merchants, tavern and inn keepers, millers, bishops, priests, nuns, white men, women, and children all held Africans in hereditary bondage. Slave ownership in Canada not only filled the need for cheap labour; it was also a symbol of personal wealth and social standing.

Colonial property law legalized, enforced and maintained the enslavement of Africans through legal private contracts that laid out transaction details (the selling, buying, and hiring out of enslaved persons), as well as will bequests in which enslaved people were passed on to wives, sons, and daughters. As James Girty, of Colchester, wrote in his 1817 will,

I also bequeath to my said son James the following six negro slaves or such of them as may be living at the time of my death, viz : Jim or James, Hannah, Joe, Jack, Betsy and Tom, and also the children which may hereafter be born of the said Hannah and Betsy. And to my daughter I bequeath my negro wench called Sall, and also a negro woman called Nancy with her five children, which said Nancy was the property of the mother of my said children and intended by her for my said daughter and also the children who may hereafter be born of their bodies or the bodies of their children respectively.

To encourage White American settlers to emigrate north, the British government passed an Imperial Statute in 1790 entitled, An act for encouraging new settlers in His Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations in America. One clause permitted white immigrants to bring in “negros [sic], household furniture, utensils of husbandry, or cloathing [sic]” duty-free.

At the early stages of white settlement in Canada, enslaved men cleared the land, chopped wood, and built homes and barns. Enslaved men and women laboured as agricultural workers on homesteads, preparing fields for planting, harvesting crops, and tending to livestock. Enslaved African women largely worked as domestic servants and minded their enslavers’ children.

Enslaved children worked alongside their parents as soon as they were able. Many enslaved men and women worked with their enslavers in the businesses the latter operated, including merchant stores, mills, inns and taverns, and even newspaper publishing. Enslaved men were trained and employed in skilled trades such as blacksmiths, carpenters, cobblers, wainwrights and coopers.

They were also employed as hunters, voyageurs, sailors, miners, fishermen, and dock workers. Slave labour was used to make products like potash, soap, bricks, candles, sails and ropes. When enslavers did not have ample work, they hired out their slaves so they could continue to reap financial benefit from their labour.

Enslaved African people laboured extensive, arduous hours and were always at the beck and call of their enslavers. Their forced labour increased the personal wealth of white Loyalist settlers, and in turn, enhanced local and colonial economies.

The Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada

On July 9, 1793, the colonial administration passed An Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude (also known as the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada). The legislation became law in Upper Canada after receiving Royal Assent. This law was a compromise between Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe and Attorney General John White, who together proposed an abolition bill, and the other members of the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council.

Six out of the 16 members of the First Parliament of the Upper Canada Legislative Assembly (1792–96) and six out of the nine original members of the Legislative Council enslaved Africans or had family members who held slaves. This legislation confirmed the slave status of those who were enslaved as of 1793 and therefore legally acknowledged the practice of slavery in the province. Contrary to popular opinion, the Act to Limit Slavery did not emancipate any enslaved persons. Nor did it prevent the sale of slaves within the province or across the border into the United States. Rather, the law prohibited the further importation of enslaved persons into Upper Canada from that date.

The law grandfathered slavery in Upper Canada. Anyone enslaved at the time of the law’s enactment would remain the property of their enslavers for life, unless manumitted by their enslavers. The legislation also held that children born to enslaved women after 1793 would be freed when they reached age 25. Their children were free at birth. This law also had provisions requiring enslavers to provide food and clothing to the young children they enslaved, and to provide security held in trust by the town warden or local church for recently freed slaves to ensure they would not become a financial burden. This latter measure encouraged enslavers to employ their former slaves as indentured servants, with renewable nine-year contracts.

When the seat of the provincial government moved from Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) to the Town of York in 1798, several politicians who relocated moved with the Africans they enslaved. As described in the walking tour I curated, Brought in Bondage: Enslaved Blacks in the Town of York, Provincial Secretary and Registrar William Jarvis and his wife Hannah enslaved three men and three women. Peter Russell, the receiver and auditor general, and his sister Elizabeth, enslaved a mother and her three children. Solicitor General Robert Isaac Dey Gray enslaved two brothers. Beyond the Town of York, enslaved Africans resided across Canada in emerging urban centres and dispersed rural spaces; many remained in involuntary servitude well into the 1800s.

During Upper Canada’s second parliament, the issue of slavery arose again. Some enslavers in the province were unhappy with the 1793 restrictions on slave ownership. In 1798, legislator Christopher Robinson proposed a bill to reverse that law, allowing white settlers to import enslaved Africans and permit white immigrants to bring their slave property to help meet labour shortages.

Robinson’s Bill to authorize and allow persons coming into this Province to settle to bring with them their Negro Slaves passed the first three readings in the Assembly by an 8 to 4 vote. However, the bill didn’t proceed any further and disappeared. Still, its introduction showed that the white power structures in Upper Canada opposed the abolition of slavery and sought to maintain enslavement to their advantage. In the ensuing years, enslavers served in Parliament until the 1820s.

As a British colony, Canada was also very much entangled in the Transatlantic slave trade. Salted cod and timber were exported from Canada to the Caribbean. Artist Camille Turner has identified 19 slave ships constructed in Newfoundland in the Slave Voyages Database. In exchange, goods produced in the slave economies of the Caribbean — rum, molasses, tobacco and sugar — were imported to Canada.

Evidence of the enslavement of African peoples in colonial Canada is documented in military records, conveyances of slaves, church records, newspaper advertisements, and account ledgers demonstrating the brutality of the objectification of African people as non-persons and commodities and the denial of their dignity and humanity.

The truth of course is that they were individual human beings: mothers, fathers, spouses, siblings, and offspring. My doctoral research, One Too Many: The Enslavement of Africans in Early Ontario, 1760 – 1834, aims to fill in the gaps and silences on the constitution and spectrum of enslavement to better understand the lives of these men, women, and children held in bondage.

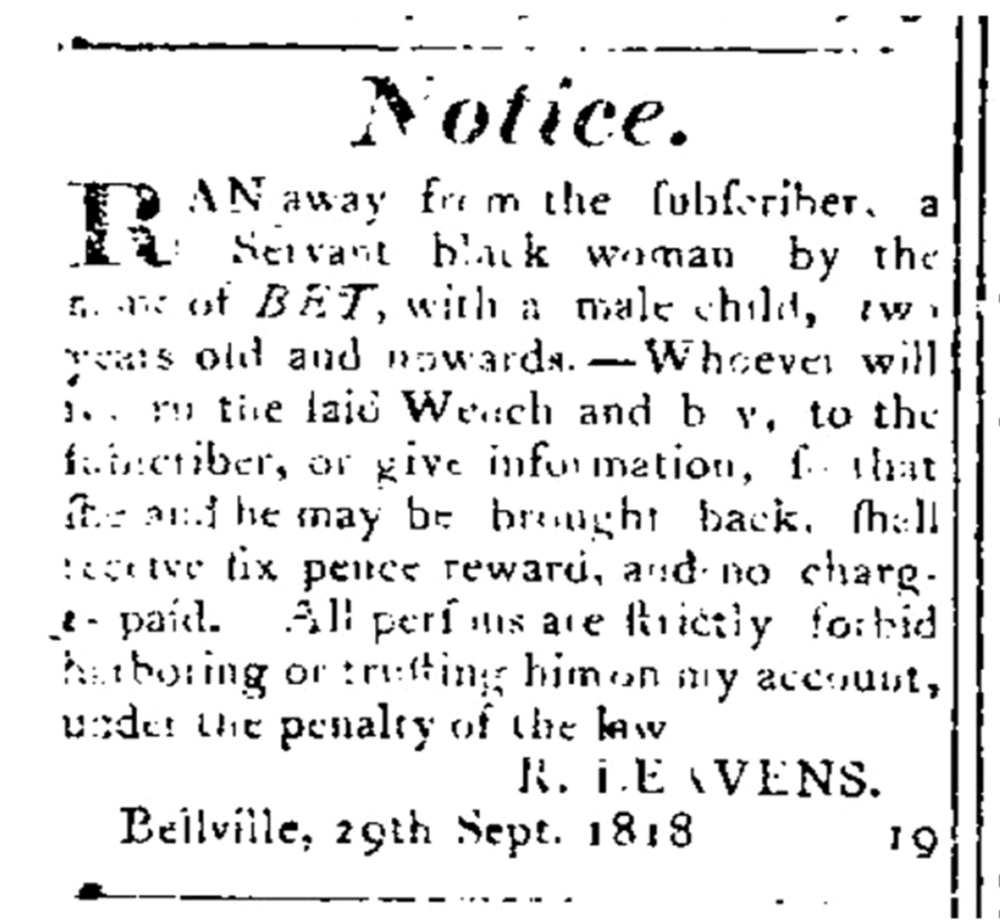

This run-away -advertisement ran for four consecutive weeks in the Kingston Gazette, September 29, 1818

Slavery was gradually phased out in colonial Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island due to a combination of factors. When a number of enslaved Africans legally challenged their slave status, a few abolition-minded judges placed the burden of proof on slave owners to prove legal ownership. Most enslavers who appeared before these judges were unable to meet this threshold. As well, slave owners were unable to keep the limited slavery laws intact or could not get legislation passed to confirm the legality of enslavement. Consequently, enslavement in colonial Canada eventually became economically impractical.

In 1833, the British Parliament introduced and passed abolition legislation. The Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies; for promoting the Industry of the manumitted slaves; and for compensating the Persons hitherto entitled to the Service of such Slaves (also known as the Slavery Abolition Act) received Royal Assent on August 28, 1833, and came into effect on August 1, 1834. The law abolished slavery throughout most of the British Empire, including British North America.

Although Emancipation Day has been commemorated since abolition, full freedom remains elusive for the descendants of the Transatlantic slave trade because the racial hierarchies and ideologies formed out of slavery persists to this day.

Anti-Black racism is a particularly pernicious, borderless, and unique form of racism that has its roots in the Transatlantic slave trade. Slavery evolved into what Saidiya Hartman terms the “afterlife of slavery,” the modern-day, virulent, enduring forms of structural racial injustice and the different forms of structural inequalities that African descended people here in Canada and in other parts of the world continue to experience today.

The 2017 U.N. working group report explicitly outlines environmental racism, over-surveillance, racially disproportionate outcomes in the education system, chronic underemployment, and the generational wealth gap that Canada’s Black communities have endured for nearly two centuries.

Canada has yet to reckon with its slave past and its enduring legacies. Trudeau’s inability to give a firm response is a metaphor for how Canadians fail to confront their own histories of racial oppression.

The silencing of the history of slavery as a tool of European colonization and the broader systemic racism that Black Canadian scholars Afua Cooper and Rinaldo Walcott accurately describes as deliberate and systematic.

Canadian historians have long downplayed the 200-plus year history of enslavement. Canada’s education system has fuelled this ignorance. In 2013, the topic of slavery in Canada was included in the learning expectations of the Ontario Social Studies, History, and Geography curriculum for the first time. However, it is only a suggested topic for grades 3 to 7. This institutional erasure has contributed to Canadians’ ignorance and denial of the realities of slavery and racism, from the prime minister to premiers to the general population. The epistemic violence of this historical amnesia and wilful ignorance is a mechanism of white supremacy to maintain the status quo, so that accountability and transformative change remain elusive for Black people.

At which point do we go beyond the empty gestures of public leaders taking a knee and institutions issuing statements of solidarity, and actually move towards an apology as a first step in the process of material redress, including reparations, to achieve racial justice?

Natasha Henry is a 2018 Vanier Scholar completing a PhD in History at York University on the enslavement of Africans in early Ontario. She is the president of the Ontario Black History Society (@OBHistory). Follow her on twitter at @NHenryFundi.

The post If Black lives truly matter in Canada, an apology for slavery is only a first step appeared first on Spacing Toronto.